I have a great job. I’m an opera timpanist, and I get to do that at the Metropolitan Opera — the biggest performing arts institution in the western hemisphere — home to the grandest of grand opera.

And I do mean grand opera. It’s basically western civilization’s most opulent expression of human drama. Almost nothing else can compare in terms of scale, scope, depth, integration, and raw emotional impact.

All of our most essential human stories are there. You can always find parallels to your own life in the great works of Verdi or Wagner, Puccini or Strauss, Mozart or…more Mozart.

The essential ingredient in all of this is drama: the examination of our human condition. We’re still trying to reconcile ourselves and our humanity to the rest of this crazy world via the great comedies and tragedies of our artistic forebears. These stories are always relevant. Our human condition is always fraught. That drama will always be there.

And one of the great things about being an opera timpanist is this: operatic timpani are agents of peak drama. Love, betrayal, vengeance, and oh-so-many operatic ways to die — at those key moments, you can be pretty sure that timpani will be involved. Maybe it’s an epic power struggle, raising a fist in defiance (Che vuol il re da me?). Maybe it’s foretelling certain doom (Siegmund, sieh auf mich!). Perhaps it’s a heart-on-your-sleeve impassioned plea (Ebben – sia pur! Via, mozzo, v’affrettate!), or a descent into hilarious chaos (Leupold, wir gehn!). It could be one of art’s most visceral displays of debauched savagery (Man töte dieses Weib!), or the justly-earned punishing fires of hell (Jetzt naht dein strafgericht!). In all of those pivotal moments, timpani are essential to the intensity of that drama.

Music is all about connection. It really gets to the heart of why any of us do this in the first place: to be compellingly and emotionally expressive, and to connect with a human being at the other end of those air molecules we’re vibrating.

And so music is all about communication. But as the performers, what exactly are we communicating?

It’s a good question. Great teachers will often say something like “your playing should tell a story.” Okay…what story? In some of the greatest works of the symphonic canon, the music is essentially abstract. The “story” of Brahms 1 or Beethoven 9 or Mahler 5 is rendered in a language that is not so specific as “Call me Ishmael.” As the performer, your “story” is really your interpretation — the layering of all of your musical choices, your style, your sound, your personality…until it hopefully becomes unified with the intent of the composer in a harmonious and convincing way. That’s the abstract storytelling of great music.

But in opera, we are telling a very specific story. Sure, there can be lots of angles to that story, many plausible interpretations, and a wide variety of meanings to draw. But the essential nature of the drama must remain intact: no matter how you play it, Elisir d’Amore won’t become a tragedy any more than Parsifal will become a comedy. And so your role as the performer is to remain faithful to that drama. The drama must inform your musical choices.

It then becomes sort of obvious when you think about it: “I LOVE YOU!” should sound different from “and NOW YOU DIE!”

As a timpanist, I have a variety of expressive parameters at my disposal: dynamics, phrasing, tone, articulation, stroke speed, beating spot, and mallet choice just to name a few. Each note I play contains conscious decisions about those (and many more) variables. For many of those decisions, however, I cannot simply depend on the printed part. There’s a lot that’s not on the page.

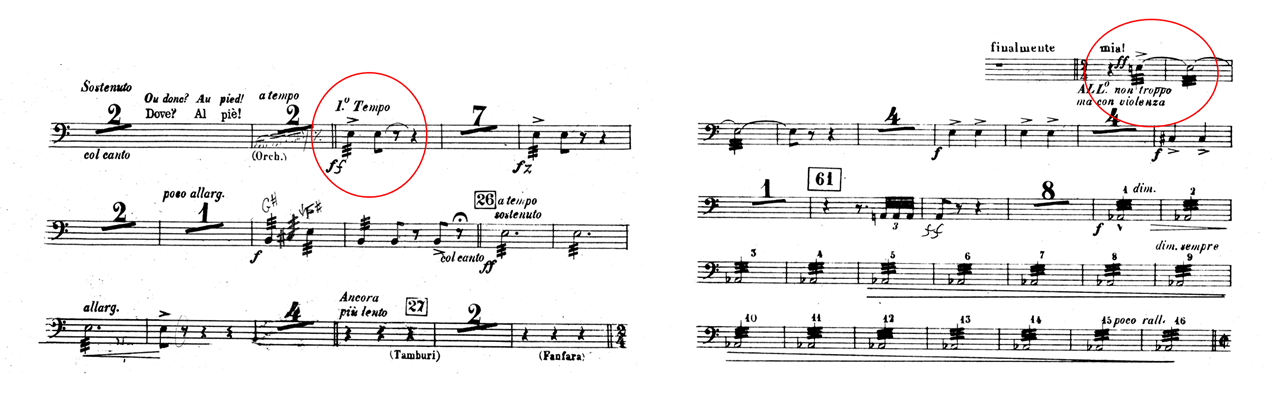

Because without the story, these two timpani parts might seem fairly similar, right?

I mean, they’re both rolls. They’re both marked fortissimo. They’re both accented. They’re both on E-natural. They’re both Italian parts. Specifically, they’re both Puccini timpani parts.

But if I just plopped down to play these parts without knowing the context, and all that registered was “timpani roll, fortissimo, E natural,” well…I would really be missing the point!

Because as it turns out, these are radically different dramatic contexts. In the first instance, we have this:

It’s a wonderfully climactic moment in Act II of La Bohème, where Marcello re-declares his love for his coquettish ex-girlfriend, Musetta. It’s fun. It’s heartwarming. It’s incredibly passionate music.

And so I try to play that passage in a way that reflects that drama: loving, warm, full, embracing, joyful. A big thick sound, lush, nothing hard or nasty or edgy.

By extreme contrast, in the second instance we have this:

Tosca is one of history’s great “fearless girls.” For most of the second act, the ruthless villain Scarpia has been torturing her love, Cavaradossi. At this point in the story, Scarpia’s proposition is this: “sleep with me, or I’m going to kill your boyfriend.” Tosca instead chooses option number three: driven to the brink, she stabs him to death.

And here, the timpani are that knife. It should sound like a blade diving into your rib cage: piercing! Sharp! Aggressive! Righteous vengeance on the tip of that steel!

If I’m doing my job reasonably well, an audience member shouldn’t necessarily notice all of these little micro-musical decisions that support the drama. It should be congruous with the drama in such a way that seems perfectly natural. It should “just fit.” As mentioned above, that emotional expression should fluently connect with a human being at the other end of that vibrating air. All of this depends on the performer’s imperative: know the story.

Do I have a methodology for achieving these different emotions and moods and styles and colors in my playing? You bet I do. I’ll be exploring that in future postings.

Until then, gioventù mia, tu non sei morta!

![]()

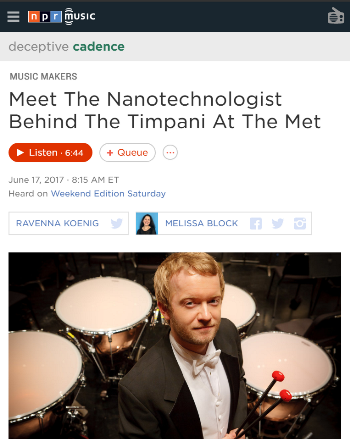

[UPDATE: This post was featured as part of a June 17th, 2017 interview with Melissa Block on NPR Weekend Edition! Listen to our conversation here:]