An Avalanche of Understanding

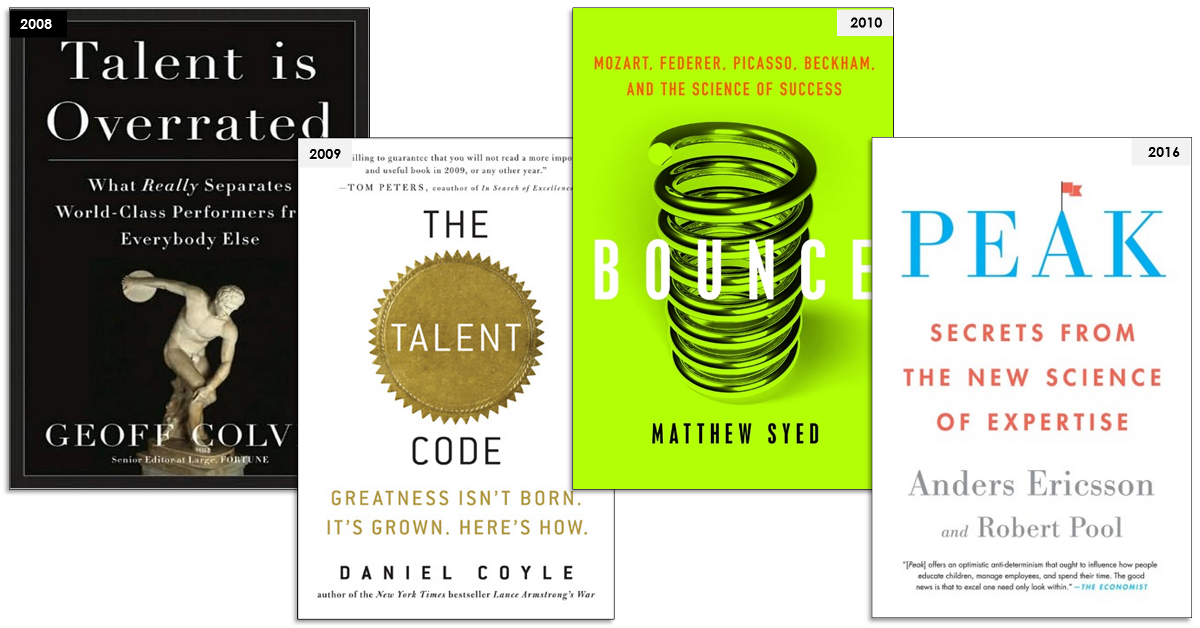

Back in 2008, I read a book that changed my life. It’s called Talent is Overrated, written by Geoff Colvin, and it’s partially based on Anders Ericsson’s research. In my previous post, I described this event as “my third inflection point,” in which I began working with John Tafoya, he recommended the book, and I subsequently embraced its practice methodologies under his guidance. That process was tremendously influential. It radically accelerated my improvement, and pointed my trajectory much higher. I want to dive more deeply into that experience, and the related books that came after Talent is Overrated.

About six months later, Daniel Coyle published The Talent Code. I devoured it. In 2010, Matthew Syed published Bounce, a third take on the same topic matter, drawing in even more research and anecdotal stories, and pointing to the same conclusions. I cruised through the audiobook of Bounce in less than two days, and then I bought a hard copy so I could scribble in the margins. Finally, in 2016, the godfather of the field published his own book; Anders Ericsson’s Peak is the most comprehensive, persuasive, and accurate presentation of these ideas to date. (Side note: in 2008, Malcolm Gladwell also wrote Outliers. It’s an interesting read, but it gets some important things wrong with respect to the research. Specifically, Gladwell created “The 10,000 Hour Rule”…and I wish he hadn’t. It woefully oversimplifies the situation, pegging expertise to a fixed number. In reality, there’s nothing special about “10,000 Hours.” Instead, it’s much better to think about “many thousands of hours,” where the ultimate total depends on the person, the context, and the quality of the practice. More on that later.)

The four books above are all very much worth reading; for anyone that is serious about their practicing, I strongly recommend them. (If you’ve read others in this vein, please note them below in the comment section!) The level of detail and practical applicability in those four books can benefit you tremendously. They represent a new avalanche of understanding about expertise, and how it’s built. They propose an entirely different way of thinking about “talent.”

It can be disorienting to experience a complete reorientation of your thinking — a paradigm shift. For literally millennia, dating back to at least the great Greek philosophers, mankind has clung to this idea of innate talents and inborn gifts. This idea is manifested so broadly that it would be absurd to try and catalog it, but just consider that Achilles, Siegfried, Anakin Skywalker, and Peter “Star Lord” Quill all share this common trait: a mystical birth that imbues them with unique and innate powers. This idea is so foundational that Edith Hamilton wrote a book about it — Mythology, standard reading in undergraduate humanities classes — which traces the “Hero’s Journey” throughout pretty much the entire western canon. It’s an idea that appears in our literature, plays, poetry, songs, opera, and art. That foundational idea is also entirely wrong.

In a strange way, that traditional notion of talent got a booster shot when Watson and Crick discovered the structure of DNA in 1953. All of a sudden, we had a scientific vocabulary that could ascribe nearly every aspect of our lives to genetic encoding…except it turns out that’s just not how it works. Geneticists have actually spent the last 64 years encountering the fundamental limits of genetic determinism. And with respect to that foundational idea of innate gifts, beginning in the 1990s and accelerating through the 2000s, researchers have been turning that traditional notion of talent upside down. The paradigm shift is well underway.

Mythology is a realm of enough depth and breadth that one can spend a lifetime studying it. I’m personally fascinated by the way we choose to relate to these myths over time, because we can draw all kinds of different meaning and lessons from these stories depending on the context. Lately, I’ve been increasingly interested in the idea that these mythological heroes are archetypes, but not prescriptions. Because let’s be real: these heroes are also deeply flawed. Achilles was an idiot; he’s invulnerable except for his heel, and yet he goes around waging war in sandals?! He’s just asking for it. Similarly, for an übermensch, Siegfried is awfully dim. (Don’t accept memory-erasing potion-drinks from strangers! DUH!) And Anakin…man, don’t even get me started on the George Lucas prequels.

Achilles, Siegfried, and Anakin are terrible models for hard-won personal growth and the incremental building of expertise. No, they’re more like collective warning signs: “Don’t go this way! This is not how to go about your own journey!” Your destiny is not set from birth. Your genes don’t shackle you to a specific path. Your journey is up to you, and decades of research can now inform the way you practice and work towards expertise. You can start by harnessing the avalanche of understanding in the pages of those four books. Again, I recommend reading them cover to cover. But here’s the Cliff’s Notes overview, because when you zoom out far enough, all four books are saying basically the same things:

First, expert-level performance in any discipline requires smart hard work — “deliberate practice” — and putting in many thousands of hours. With sufficient deliberate practice, anyone can become much better. With overwhelming amounts of deliberate practice, one can achieve mastery.

Second, many thousands of hours of deliberate practice is by no means a guarantee of “success,” only that you’ll improve dramatically. “Success” is a loaded term, and a concept intimately connected with outcomes that we cannot fully control. In my first post, I encouraged aspiring musicians to focus on process rather than outcomes. For me, it was essential to spend all of this time and energy for the love of refining my craft rather than the goal of “winning that big job.” Because here’s the reality: there are so many extremely accomplished musicians out there that “winning that big job” is not something you can count on. With enough deliberate practice, and sticking with auditioning long enough, your odds will definitely improve. But they’ll never hit 100%. So there’s a big difference between “expertise” and “success.”

Third, “Talent is Overrated.” Any perceived-advantages manifested in youth become irrelevant over the long run. What matters much more is the discipline required to apply deliberate practice over the many required years, and all evidence points to the fact that qualities like discipline, focus, and concentration are trainable skills akin to exercising muscles, and are not linked to any specific genetic inclination. A prominent example of this can be found in chess, where researchers have studied the IQs of tournament players and grandmasters. The conclusion? There is no correlation between a grandmaster’s ranking or tournament performance and their IQ. In fact, recent studies have begun to demonstrate an inverse correlation, with lower-IQ players actually doing consistently better over time. How is this counterintuitive result possible? For anyone who teaches, it’s empirically obvious that some students “pick things up” faster than others. “Picking up something quickly” is a short-term phenomenon, linked to short-term memory, and generally correlated with IQ. But how much impact does this have over the long run? What’s the influence over the 10-15 years it can take to achieve real mastery? Not much, it turns out. These same studies have shown that, among chess grandmasters, lower IQ is actually a slight advantage because when you’re younger it forces you to practice harder and more efficiently for more hours. That’s precisely the kind of deliberate practice which is critical for developing the “mental representations” (elaborated below) on which chess mastery depends. Other studies have now shown similar results in other fields, and it’s easy to see how the principle can and will hold true for musicians as well.

Fourth, deliberate practice comprises a set of core scientifically-studiable attributes that are the same across nearly every field imaginable. We’ll get to those attributes below.

Mozart the Human

When confronted with this new paradigm of talent, many people reflexively point back to figures like Einstein or Mozart, saying “oh yeah? Explain THAT. Clearly they were born geniuses.” Among composers specifically, the intervening centuries and the inertia of the old notion of talent have elevated Mozart to mythical status. (It’s easy to imagine Yoda landing in Vienna in the late 1750s proclaiming, “Strong with the force, this one is.”) But was Mozart a genetic genius? Does the historical reality of Mozart contradict our new understanding of how expertise is cultivated?

When confronted with this new paradigm of talent, many people reflexively point back to figures like Einstein or Mozart, saying “oh yeah? Explain THAT. Clearly they were born geniuses.” Among composers specifically, the intervening centuries and the inertia of the old notion of talent have elevated Mozart to mythical status. (It’s easy to imagine Yoda landing in Vienna in the late 1750s proclaiming, “Strong with the force, this one is.”) But was Mozart a genetic genius? Does the historical reality of Mozart contradict our new understanding of how expertise is cultivated?

Mozart was a human being, not a god. He was born in 1756, to real human parents: Leopold and Anna Maria. Now, many musicologists consider Mozart’s first “mature” work to be the 14th Piano Concerto (E flat major, K.449). Mozart wrote a ton of stuff before that, but a lot of it was derivative; K.449 marks a starting point for the output history would remember, and the works that would go on to define him. And Mozart wrote the Piano Concerto No.14 in 1784. 1784. Let that sink in for a moment: Mozart was already 28 years old when wrote it. In spite of beginning musical studies at the age of 4 with his father Leopold, one of the leading musical pedagogues in Europe, Mozart would put in 24 years of deliberate practice before he produced anything that history would truly consider “great.” If anything, Mozart was behind the curve!

So, no, the historical reality of Mozart does not contradict our new understanding of talent. Moreover, it should in no way diminish Mozart’s genius. For me, it enhances it…because Mozart’s genius wasn’t gifted, it was earned.

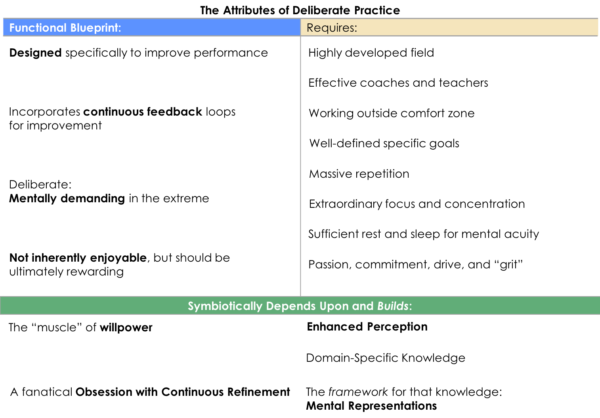

The Attributes of Deliberate Practice

As discussed above, the new understanding of talent revolves around the implementation of deliberate practice over many thousands of hours. It also hinges on the notion that quality of practice is at least as important as quantity; a large quantity is necessary, but it only counts if it’s the right kind.

All music students are told what to practice; very few music students are told how. Specifically, very few music students are told, “this is how you practice effectively, efficiently, and with the greatest impact.” It’s peculiar to me that this has not emerged as a higher priority in music pedagogy. (It’s like telling an aspiring chef “You need to make a soufflé,” and then snatching away the recipe saying “I’m sure you’ll figure it out.”) By contrast, the four books above argue that how you practice is actually the most important thing. So what’s the “right kind of practice?” Here’s a starting point….

Attributes of Deliberate Practice:

- Deliberate practice is designed intentionally to improve performance, and to be extensively repeated. It’s specifically targeted, non-haphazard, and each session has clear-cut goals focusing on identified weaknesses.

- Deliberate practice incorporates continuous feedback loops for improvement. Feedback can take many forms, but among the two most important for orchestral musicians are mock auditions and self-recording.

- Deliberate practice is grueling, and demands the utmost focus and concentration. It should not be easy. When done right, it’s mentally exhausting.

- Owing to the intensity of focus required, deliberate practice physically drains you and there is an upper-limit to how much you can effectively practice in one day. This will vary from person to person, but in general it’s about 3-5 hours maximum.

- Consequently, deliberate practice also requires physical replenishing through sleep. (Practicing chronically sleep-deprived is incredibly ineffective.)

- Deliberate practice is, by definition, a solitary activity. It’s also a type of problem solving focused on specific skills, and it’s inherently self-directed. However, everyone will encounter hurdles, bottlenecks, and plateaus, and that’s why you’ll need to rely upon effective teachers, coaches, and mentors to help you solve the problems you don’t yet know how to solve by yourself.

- Applying years of solitary deliberate practice requires incredible commitment, drive, and intrinsic motivation. Ideally, your passion springs from a love of the art form and a dedication to refining your craft within it. Over time, you become obsessed with continuous refinement, pleased with your progress but never fully satisfied, and always searching for ways to make it just a little bit better.

- These accumulated years of deliberate practice will give you enhanced perception. Whether it’s the grandmaster’s ability to view a chess board and instantly analyze strengths / weaknesses / lines of attack, or an experienced orchestral musician’s ability to hear their part in a chord and instantly adjust their intonation a few cents for harmony that’s resonantly in tune, growing expertise enables finer discriminations and more acute sensory input. Your ears hear more. Visual images convey more information more quickly. And this enhanced perception inevitably makes you pickier about your own performance, pushing ever upward for that next level of refinement.

- Finally, all eight attributes above build upon and require “sophisticated mental representations.” Other researchers have called this a “framework of domain-specific knowledge.” Plato would have called it “the ideal world of forms.” The Sherlock Holmes from the BBC/PBS calls it his “mind palace.” In orchestral music performance, this encompasses everything from music theory and music history to our sense of cross-genre aesthetics. For example, my 2017 “ideal version” of the Beethoven-9th-Symphony-1st-movement-coda timpani excerpt exists at a level of detail, refinement, and understanding that is staggeringly more sophisticated than my 2007 “ideal version.” The refinement of those intervening 10 years involved everything from my process of score-informed musical decision-making to my perception of tone and my overall “artistic vision.” We can all relate to this: the more you do a thing, the finer degrees of detail you’re able to perceive, and the more discriminating you become. This informs your “ideal,” and that union of perception and knowledge creates an increasingly sophisticated mental representation.

There’s obviously a lot to unpack in the list above; each of those attributes will get its own blog post in the coming months. For next time, we’ll launch into “Practice Session Design.” Until then, find a DeLorean, set it to the year 1760, accelerate to 88 mph, and tell little Wolfgang to pick up the pace!

![]()