(The Attributes of Deliberate Practice: Continuous Feedback Loops)

You Won’t Get Any Better, and You’ll Stop Caring

In 1996, Ethan and Joel Coen went bowling. Or, more specifically, their film Fargo had just been released, and after its opening night showing they hosted the after-party at the Bryant Lake Bowl in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was there that they cooked up the idea for their next movie — one which would ultimately rank among the most iconic cult classic movies of all time: The Big Lebowski.

Lebowski turned 20 a few weeks ago, and at this point I’m certain I’ve watched it at least 40-50 times, to the point where I can gleefully quote entire scenes by memory, reveling in the absurdity and the rhythms of its immaculately crafted dialogue. (It’s nearly operatic: there are three clearly defined acts with musical preludes to each, a ludicrous plot, and verbal leitmotif peppered throughout the script. A work of art, IMHO.)

And the characters: Lebowski’s characters and cast are legendary. Jeff Bridges, John Goodman, Steve Buscemi, Julianne Moore, Philip Seymour Hoffman (R.I.P. 😔)…I mean, c’mon! Dream team!! In particular, John Turturro plays a character who has only six lines in the entire movie (exactly 142 words, for anyone who’s counting). But in terms of movie character “impact ratio” — the memorability of the character divided by their amount of screen time — I submit that Turturro’s character has the highest impact ratio of all time.

And Turturro’s character is a bowler. That guy can roll, man.

You Gotta Know Whether You Hit the Pins

Imagine your practice session as bowling. Imagine that each excerpt is a frame, and each bowling pin is one of the trickiest licks in that excerpt.

Now put yourself in that moment: there’s all of the preparation that’s gone into your deliberate practice. You lace up your shoes. (You note the Gypsy Kings’ cover of “Hotel California” playing in the background.) You tug up your socks, and then lightly dry your hands over that weird venty-thing that all bowling alleys have. You pick up your ball, adjust your posture, swing your arm back, step, step, step, STEP, THROW!

Your ball is hurtling down the lane, great trajectory, great spin…

.

…but then your ball disappears behind a curtain. Next frame.

After the game, your two friends ask “Dude, how’d it go?”

You reply, “Well, man…I have no idea!”

THAT is practicing without feedback. Practicing without feedback is like bowling through a curtain: you won’t get any better, and you’ll stop caring.

That quote comes from Steve Kerr, former Chief Learning Officer (CLO) of Goldman Sachs, via Talent is Overrated. It’s a brilliant analogy. It packs substantial wisdom into those 18 little words. It also prompts a question: what is feedback? Or more specific to my Attributes of Deliberate Practice series: what are continuous feedback loops?

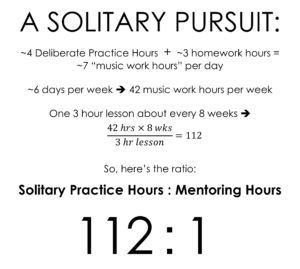

Feedback can take many forms; three of the most important for orchestral musicians come from teachers, mock auditions, and self-recording. The feedback you receive from your teacher will get its own upcoming post, as will how to approach mock auditions and best harness their learning potential. But for now, consider that among these three types of feedback, one of them utterly dominates the others in terms of overall time and energy investment. Can you guess which one? Here’s a hint:

Now, my particular circumstances of being out of school and focused on auditioning were fairly extreme. But for anyone, despite the ensemble nature of orchestral music, the vast majority of your time spent refining your craft will be in solitary confinement. Deliberate Practice is, by its very nature, a solitary pursuit. Especially once you’re out of school — once the training wheels are off, and you no longer can rely upon that weekly accountability check-in with your teacher — your practicing will become a nearly monastic activity of isolation. And that’s okay! That’s how it should be. But considering those different ways you can get feedback, and considering the amount of time you’ll be spending by yourself, it probably makes a lot of sense to maximize the amount of feedback you can receive while in isolation…right?!

For me, 99.1% of my time was spent practicing on my own. Therefore, it was absolutely essential that I maximized the amount of feedback I could give myself during that time.

Self-Recording: The Best Way to Give Yourself Feedback

Here’s the part where I make a confession: I am both embarrassed by and ashamed of how long it took me to figure this out. In world history, we have B.C. and A.D. — year zero marking a point where “there was everything before that, and then everything after that.” In my own personal history, I have B.S.R. and A.S.R. — “Before Self-Recording” and “After Self-Recording.”

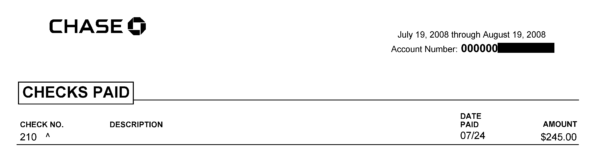

In fact, I can tell you that “0 A.S.R.” was July 24th, 2008. My guitar-player friend, Dave Schwartz, was working at a music store, and he told me he could get me a big discount on “one of those cool new digital recorders that saves directly to flash [SD card] and has great microphones.” “Awesome,” I replied. “Sign me up. Here’s the check.”

A few days and $245 later, I had my first Zoom recorder. From that point onward, I was leaving behind my prehistoric practicing life (B.S.R.), and entering a new epoch — the A.S.R. era of self-recording.

“WAIT…” you might be thinking. “Are you really comparing a Zoom recorder to the Messiah? The King of Kings??” Well, for me it was absolutely revelatory. Embracing the teachings of that device was probably the single most important thing I ever did for my practicing and audition preparation. It was…my salvation. So, yeah:

And yet, so many people practice hundreds or thousands of hours with virtually no feedback whatsoever. Thus, as long as I’m shaming myself, let me ask for a show of hands: dear readers, are you fully taking advantage of the water-to-wine-like miraculous power of self-recording? Are you honestly using your recorder during every practice session, i.e., at least 15-20 times per week?

Yeah…that’s what I figured. And don’t worry — you’re not alone. For the last few years, I’ve been asking this same question to rooms full of orchestral musicians at some of the best music schools in the country, and the results are astonishingly consistent: a handful are already self-recording, an even smaller number do it regularly, but most are not doing it nearly enough.

From my current perspective, this seems insane. I fully acknowledge that it took me far too long to figure this out…but to be fair, the emphasis on feedback prescribed in Talent is Overrated didn’t exist during the early years of my musical training. Also, the technology was cumbersome for a long time; I distinctly recall hauling my ungainly minidisc recording microphone-contraption up into the balcony of Symphony Center in Chicago so that I could capture some of our Civic Orchestra dress rehearsals for subsequent evaluation.

But that was then. Now the research demonstrates the obvious necessity of self-recording, and the technology is readily available and affordable. And yet, only a fraction of young orchestral musicians are truly harnessing its power. Why?

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this conundrum, and I believe it boils down to a fundamental human flaw: ego. To me, ego is like the friction of craft-refinement — it finds a nearly infinite number of ways to slow down our progress. It’s like the air-friction you face when trying to run a race in a 30 mile-per-hour headwind. Ego is the improvement killer.

In my previous post, I described the necessity of “honestly assessing your weaknesses, and focusing intently on improving those.” Easier said than done. Because your ego will rear its ugly head in the process. The reality of your own weaknesses are rarely more vivid than when you hear them in your own playbacks. The recorder doesn’t lie, and this can be extremely difficult to confront. Initiating the ritual of self-recording can be emotionally shredding; you’ve probably had this certain concept for how you think you sound, but all of a sudden this brutal little device pops that bubble. It’s tough. I get it. I’ve been there.

But here’s the good news – that’s only the initial phase. And just like training for a 5k if you’ve been sedentary for years, the initial phase will be painful…but you’ll get through it. It won’t take that long. And once you’re on the other side, you’ll be so glad you did it: self-recording is a secret weapon, and if there’s only one thing that aspiring musicians take away from these blog posts, I hope it can be incorporating self-recording into daily practice.

If You’re Not Self-Recording, You’re Not Deliberate Practicing

That’s because one of the essential attributes of deliberate practice is “continuous feedback loops.” If you’re spending hundreds of hours on your own, without a daily teacher and without self-recording, then you fundamentally lack a continuous feedback loop.

Feedback loops have a very specific definition in science and engineering; I used to work with them all the time, and they’re integral to the function of one of my favorite toys, the Atomic Force Microscope. But we encounter them all the time in daily life too: does your house or apartment have a thermostat? That’s a feedback loop: it sets a target temperature, measures what’s going on (feedback), and then adjusts the system accordingly to get closer to that target. Do you use google maps’ driving directions? That’s a feedback loop too: it sets a destination, uses your GPS locator to track your progress, and offers course-corrections along the way. The refinement of our musical craft should be no different. In my previous post, I discussed the design and intention of your practice session; that’s the equivalent of setting your target, and your continuous feedback loop measures whether you’re making progress toward your target. I also stated that “deliberate practice involves well-defined and highly specific goals.” Well, it’s very difficult to know whether you’re achieving those goals without feedback to verify it! It’s one thing to feel like you’ve made progress; it’s another thing entirely to have truly objective proof. (i.e., It’s one thing to feel like you’ve knocked down some bowling pins; it’s another thing entirely to see whether you did!)

Furthermore, my previous post described the necessity of repetition: “well-designed deliberate practice is crafted for massive repetition.” But here’s the thing: while repetition is required, sheer repetition alone is not enough. That repetition needs to be smart, and driven by feedback. Repetition without feedback is essentially the same as hurling that bowling ball down the lane through that curtain, over, and over, and over again. Repetition only counts if you’re getting feedback on whether your practice techniques are being effective. Your efforts need to adapt; your practice will require modification in response to that feedback.

The audio archive of your self-recording can then become a gold mine. Subsequent posts will discuss how you can most effectively mine that treasure trove, but for now suffice it to say that you’ll be re-listening to recordings of yourself many times, each time focusing on a certain dimension of your playing. You’ll be cultivating an extreme pickiness with respect to your own sound and style. And you’ll be doing this with an understanding how all of these variables translate to the other side of the audition screen, because some aspects of musicianship are subjective, but some are not — some are entirely objective, and measurable, and quantifiable. When it comes to time, rhythm, and intonation, well…that’s NOT just, like, your opinion, man!

When it comes to auditioning, self-recording will help you focus on all of the objective variables that end up getting most people cut. Because, to reinterpret a phrase from the sagely Walter Sobchak:

We’ll elaborate those rules in future posts. Until then, catch ya later on down the trail.