(The Attributes of Deliberate Practice: Effective Teachers, Coaches, and Mentors)

Proceed with Gratitude

My 5th grade teacher was Mr. Shermock. His full name was Jim Shermock, but like so many other students now out in the world, I could never imagine calling him by his first name. The indelible imprint he left on my life has meant that, no matter how far I’ve gone beyond 5th grade (or high school or college), my feelings of gratitude and respect have coarsed along as powerfully as a subterranean river. Hence, Mr. Shermock.

Much like my own parents, he was endlessly supportive and fully dedicated to stoking curiosity, creativity, and sophisticated thinking. So it is with sadness that I need to use the past tense: I just learned that Mr. Shermock passed away on August 31st.

With the new school year and opera season underway, I had already been thinking a lot about the astronomically inestimable value of teachers; reflecting on Mr. Shermock has helped focus those thoughts. I’ve written a lot so far about my own necessarily-grueling trajectory as a performer, but on the other side of that coin are the teachers I’ve been fortunate enough to work with along the way. Thinking about their traits, their impact, their gifts to the world, and their gifts to the future…all of that is frankly overwhelming. So I’d rather focus on my personal experience of teaching, both as a former student and in my growing role as a teacher.

Because teaching is hard. Just like with masterful performers, masterful teachers make it look effortless. There is a spontaneous-seeming grace to their teaching…but it’s practiced. Deliberately so. And great teachers have moved beyond mere mastery of the material — they possess the ability to propagate that mastery out to other disjunct human minds. It can seem like magic.

I remember Mr. Shermock’s classroom vividly. I can still perfectly visualize the large poster he’d installed over the classroom door: it read “TRANSFER.” “Gang,” he said, “you’re going to learn a lot of things in school, and in your life. It will be all the more fulfilling if you can transfer what you learn to other areas of your life. Other skills. Other interests. Make connections between the things that interest you. Your life can be a rich web.”

I’m still astonished when I think about that sermon-like moment. It was the very first day of 5th grade. In less than 15 seconds, Mr. Shermock harnessed that occasion, imploring us to lead meaningful lives. I feel a twinge of pain that I never got to thank him for that, because it stuck with me in a profound way. At its core, Mr. Shermock’s TRANSFER precept is not only the basis for my liberal arts education — it governed my personal implementation of deliberate practice, transferring my scientist skills of well-documented failure to the craft of timpani. I am thankful for Mr. Shermock every single day.

The Second Greatest Teacher of All

One of my favorite moments in The Last Jedi is when Yoda's force-ghost appears to Luke, chastising him thusly:

Heeded my words, not, did you. ‘Pass on what you have learned.’

Strength…mastery…umm-hmm.

But weakness, folly…failure also. Yes, FAILURE most of all.

The greatest teacher, failure is.

Sitting there in the movie theater on opening night, I gasped audibly: it was another 15 seconds of high-potency wisdom, this time delivered via a Shermock-like ancient green puppet-ghost. The idea encapsulates so much of what I had experienced and embraced in the world of deliberate practice: the primacy of failure and its twin sibling constructive feedback, leading to detachment from outcomes by instead focusing on process.

Feedback thrives on failure as its input. And failure is most meaningful when analyzed and contextualized. This symbiotic relationship is the driving force of deliberate practice. (Recall the Kerr quote: “Practicing without feedback is like bowling through a curtain: you won’t get any better, and you’ll stop caring.”) Feedback and failure are like the binary twin stars illuminating a Tatooine sunset, working together to promote progress and growth.

But if failure is the greatest teacher of all, then I would definitely argue that the second greatest teacher of all is a great teacher. Because while failure is necessary for growth, it is not sufficient. We need teachers. Great teachers. Teachers are an essential part of our journey, because the reality is that no one gets there on their own.

I sure didn’t. Whether it was Mr. Anderson reading to us from Bridge to Terabithia, Mr. Finnegan expounding on literature like John Keating from Dead Poets Society, Mr. Sinks urging our AP European History class to “follow the money,” Mrs. Baker elucidating Moby Dick and coaching our academic teams, Dr. Nimmo conducting the Gustavus Band across Norway, Dr. Wright teaching our jazz band how to really swing, Drs. Niederriter, Saulnier, Mellema, and Huber teaching me how to think like a scientist, Mr. Friesen unforgettably conducting the final measures of Sibelius 2, or Chaplain Johnson and Dr. Amamoto helping me write my senior paper about my then-confusing dual nature as a scientist and musician…it was not a solo journey.

I owe so much to my teachers: those noted above, the timpani-specific mentors I’ll detail below, and all the others I ran out of space to include. I am who I am because of them. I cannot imagine life without their influence.

Seeing You in Ways You Can’t See Yourself

Most of the attributes of deliberate practice revolve around your relationship with yourself: stoking intrinsic motivation, achieving a healthy and productive dialog with your inner-critic, channeling your inner-critic into constructive feedback, and logging thousands of hours of deliberate practice. But once you’ve embraced the need to fail and improve via constructive feedback, effective teachers are absolutely integral to deliberate practice — they see (and hear) you in ways you cannot see yourself, and they’ve already solved problems you don’t yet know how to solve.

So teachers are a key area where it’s not just about your relationship with yourself — it is decidedly about forming a mentoring relationship with another human being. An experienced and masterful human to be sure, but an imperfect human nonetheless. This naturally implies that “fit” is a really important issue; not all students will be compatible with all great teachers. Personality, learning style, and temperament are big factors when assessing this relationship.

Before diving too much further into what deliberate practice really means for you and your teachers, it's worth noting that I came at this in a highly unorthodox way. Most of the time, students audition for music schools (i.e., specific teachers), and the teachers choose which students they want to work with. I did the opposite: I auditioned my teachers.

Lest this sound too audacious, recall the situation I was in: I was living in Chicago, working full time as a scientist at a nanotechnology company by day, and digging into orchestral timpani performance by night. I had auditioned my way into the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, but after getting quickly cut in my first few professional auditions, it became obvious that I was nowhere near the level needed to realistically contend for those principal timpani jobs. I needed guidance. I needed next-level mentorship. I needed a freakin’ teacher!

Initially, I considered quitting my nanotech job and going back to graduate school for music performance. But then I started asking around with my friends in Civic who were already in master’s programs at DePaul, or Northwestern, or Roosevelt: “What are you actually doing in your master’s degree?” The important priorities emerged readily: performing in ensembles, studying with a great teacher, and practicing their asses off. It was at this pivotal point that I realized, “You know what? Maybe I can just do it myself….”

I henceforth committed myself to the “Haaheim D.I.Y. master’s degree.” I had no idea how important this would become, but I could detect a vague glimmer of certain advantages I might possess, in spite of what some would’ve considered a harebrained scheme. For one thing, I was already accumulating excellent experience playing timpani in multiple ensembles, and my day job afforded me the resources to acquire my own timpani and carve out physical space in which to practice them. For another, practicing my ass off was just a matter of disciplined time management. And finally, I realized this setup meant I could pursue that path indefinitely. I could invest in the process because I wanted to, as opposed to desperately feeling like I needed to. My efforts would not have an expiration date.

All I needed was a teacher. Or teachers, because the more I considered it, the more I realized that the Haaheim D.I.Y. approach didn’t shackle me to any one school or teacher. I could play the field, and glean helpful feedback and instruction from the best in the business. Moreover, my job afforded me the ability to fly out of town and take lessons from great timpanists in far-flung cities. So that’s what I did: I sought out many of the most prominent timpanists in the United States for private lessons. Nearly all were perfectly amenable to this arrangement.

It was during this time that I really started to appreciate the nature of teacher-student compatibility, because almost by accident I’d developed a litmus test for the teachers I was “auditioning.” Inevitably, a great timpanist would demonstrate something new or different, and I’d remark, “Whoa! Cool! Tell me more….” They would elaborate. I’d then respond, “so…why do you approach it that way?” Sometimes they would respond with “because that’s how my teacher did it,” or “that’s just how it’s done,” or “because I say so.” That’s perfectly fine; that works for some students. But sometimes my potential-teacher would respond with, “I’m so glad you asked, because this points to a larger issue we can discuss.” To me, that was pure joy. Because that’s how I’ve always approached music. I’m less interested in rote instruction than I am in exploring method systems and frameworks of thinking. I’m especially interested in how those frameworks connect to the aesthetics of different composers, styles, and time periods. So, “I’m glad you asked” was a strong indicator of open-minded compatibility.

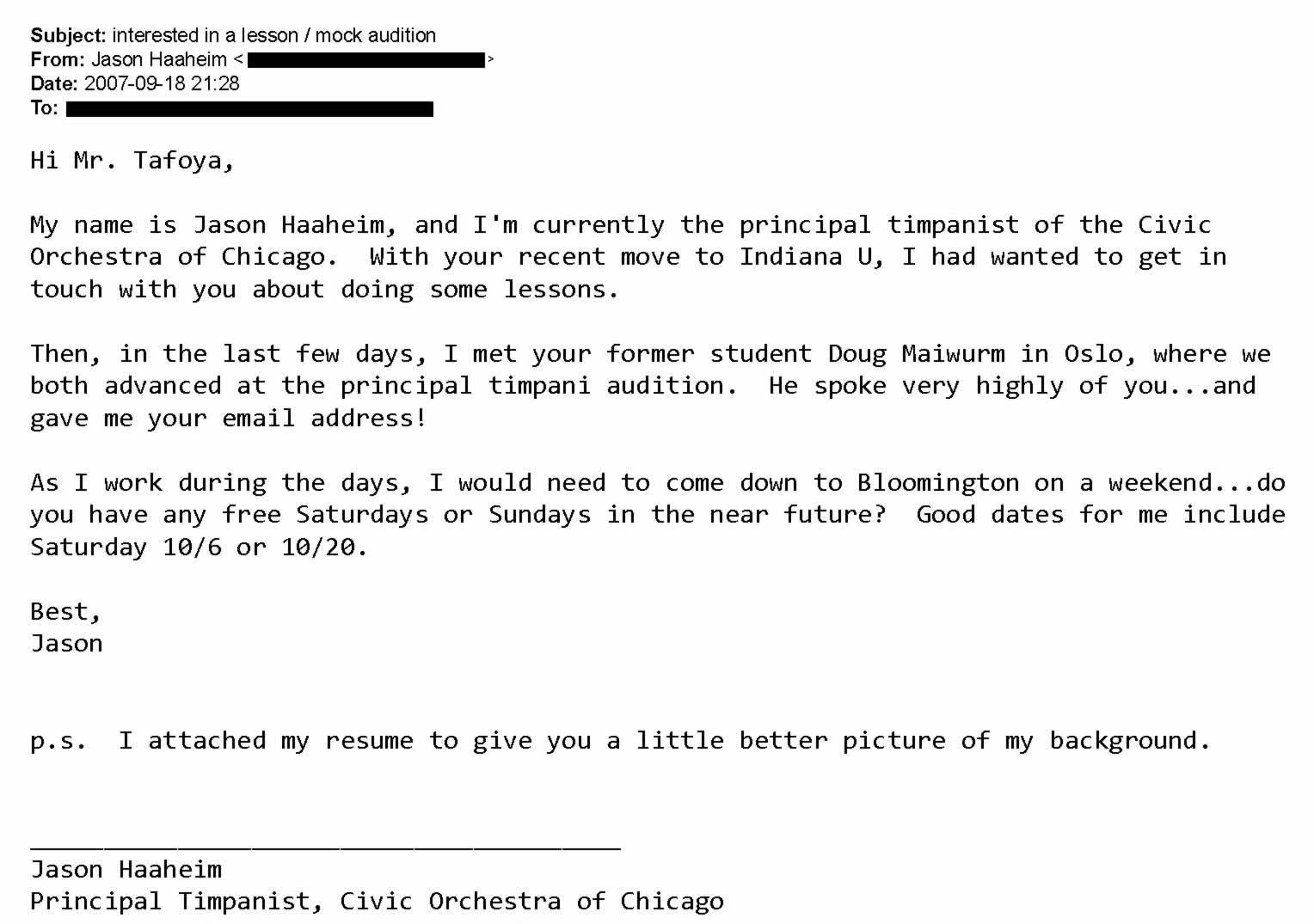

So it was with John Tafoya. I sent him the following email back in September of 2007:

He replied that he’d be happy to arrange a lesson, and we settled on Saturday, October 6th. Now, John actually began his musical training on the violin, switching to percussion while an undergrad. During that first lesson, he started talking about playing timpani like a string instrument…and it blew my mind. Not only that, we really clicked, and I couldn’t wait to schedule our next lesson.

I’ve previously chronicled the “inflection point” of those next few months, specifically when John recommended I read Geoff Colvin’s Talent is Overrated. It was revelatory, and in the subsequent months and years I would fully embrace the concepts of deliberate practice amidst John’s expert coaching, all while continuing to travel and seek feedback from everyone else I could. Another of those excellent timpanists was Dean Borghesani, a friend of John’s to whom he was happy to make an introduction. My first lesson with Dean was Sunday, June 27th, 2010, in the basement studio of his lovely home in Milwaukee, and it was a marathon session: for nearly 5 hours, we jammed on timpani rep, discussing, deconstructing…and totally clicking. On my drive home, I was both exhausted and elated. Five hours is a long time to be “on” during a lesson, but it was fantastic, and I was pretty sure I’d found another indispensable timpani mentor.

Now, while John and Dean had the most direct and recent impact on my timpani training, we are all compilations of a vast amount of accumulated teaching feedback, and there were many fine percussionists and timpanists that helped me along the way. My very first percussion lessons were with Bob Adney at the MacPhail Center for Music in Minneapolis, and it’s a sincere privilege that I get to continue working with Bob in presenting the Northland Timpani Summit. I’d also previously noted the Aspen Music Festival as a major inflection point; that summer, Jonathan Haas opened my eyes to the excitement and dramatic potential of orchestral timpani, and it’s another privilege that I now get to call him a colleague at NYU (where I teach a timpani-focused master's curriculum, and host the Artful Timpani Auditioning seminar). And to perfectly illustrate the idea that “impact” doesn’t always correlate with time, I only got to meet Cloyd Duff once; I attended a masterclass he gave in Minneapolis in the fall of 1999, only a few short months before he passed away. But that class — and especially the brief conversation I had with him afterwards — had a profound impact on the ways in which I would go on to think about timpani sound production. Cloyd was a true gentleman: warm, charming, and still possessing a razor-sharp artistic intellect in the final months of his life.

It would be easy to stop here, saying “seek out teachers who are excellent instrumentalists, wonderful human beings, and people with whom you temperamentally ‘click’ well.” That’s all true, and necessary…but it’s not the full story. What makes people like John Tafoya and Dean Borghesani such excellent teachers? It’s worth drilling into, because it serves to highlight additional attributes of deliberate practice.

First, it’s worth clarifying that, for me, John and Dean represented a mentoring “power couple” precisely because they came from different timpani lineages. All instruments have different “schools,” playing philosophies, and “camps,” and while this is to be expected, I’ve always been someone who shies away from the constraints of orthodoxy. So I was keenly interested in blending “the best of all worlds,” noting that there are in fact very few areas of timpani pedagogy that are mutually exclusive. Not all teachers would support this sort of approach, but John and Dean certainly did, and that was incredibly valuable for me.

Next, an inevitable consequence of pursuing timpani via my “Haaheim D.I.Y.” program was that I knew I wasn’t going to implement every single thing each teacher told me. One of the strengths of our artistic culture in the United States is the diversity of opinions, approaches, and styles; prominent teachers will never agree on everything…and I believe that is actually a good thing. Diversity leaves room for progress, growth, and evolution. It also forces students to start thinking for themselves. The further along you get in instrumental training, the more important it will be to assert your own artistic personality; the most convincing artistry is authentic and personal, and not just a cloned reproduction of whatever your teachers have conveyed. Besides playing for a variety of teachers, you will also play mock auditions for a variety of other peer musicians whose instincts you trust. And you are guaranteed to receive conflicting feedback, sometimes from the same jury on the same day. (Juror 1: “I thought it was played too timidly and conservatively.” Juror 2: “Too brash and over the top.”) One measure of artistic maturation is being able to sort conflicting feedback, first distinguishing factors that are objective (time, rhythm, intonation, clarity) from those that are subjective (phrasing, tone, style, personality), and then sorting through the subjective comments, absorbing those that fit your artistic identity, and leaving others on the shelf. In the moment, you must always accept all of the feedback graciously and without resistance or defensiveness; later, you’re free to regard or disregard it as you see fit.

So, knowing that it wasn’t simply “implementing every exact thing they told me” that made John and Dean excellent teachers, what was it?

Most importantly, teachers are a vital source of corrective feedback, because they see (and hear) you in ways you cannot see yourself. Teachers will diagnose problems that have gone thus far undetected in your self-examination. Better yet, they should know how to solve those problems. This speaks directly to a topic I previously covered: design and intention. Until you've achieved a sufficient level of self-awareness and self-analysis, the design of your practice process almost certainly requires coaching. This is a key to interacting effectively with teachers, and making the best of both your time and theirs: excellent teachers should be helping you design your practice to address your highest priority unsolved problems. You can proactively capitalize on your teacher’s expertise by moving beyond simple “diagnosis” and into problem solving. For example, I never wanted to walk into a lesson where a teacher would surprise me by saying “that spot is rushing.” I wanted to diagnose that ahead of time by recording myself, and then walk into the lesson asking “how can I design my practice to avoid rushing that spot?”

As your teacher helps you solve problems you cannot solve yourself, the definition of “what you should be able to solve yourself” will be constantly expanding. Because one of the other attributes of great teachers is that they’ll help you to eventually become your own best teacher. Recall: the process of refining your craft will last a lifetime, but the timeframe in which you’ll be studying with your teacher is substantially narrower. There will inevitably come a time when you don’t have that teacher to rely upon for consistent feedback. Continued improvement is only possible if one of your goals is to become excellent at self-teaching — setting aside your ego, unemotionally assessing your weaknesses, and brainstorming ways to address them. An essential part of continuous refinement is giving yourself the most honest and necessary feedback possible. So while some teachers might say “I taught him everything he knows,” a great teacher can say “I helped him teach himself.”

In Peak, Ericsson writes that the “most important lesson [students] gleaned from their teachers is the ability to improve on their own….” Even if you’re already studying with one of the best teachers in the country – maybe especially if – the vast majority of the work you do is going to be on your own. Measured hour-by-hour, the process of deliberate practice is largely self-directed. My case is a bit extreme, but it remains illustrative: between 2008 and 2012, I was taking a timpani lesson every 1-2 months. In between, I was pushing my physical limits of practice endurance, peaking at roughly 35 hours per week. Even factoring in the multi-hour lessons offered by my teachers who were extremely generous with their time, this worked out to a ratio of roughly 112:1 — for every hour I spent with my teacher(s), I spent 112 solitary hours in my home studio. In other words, 99.11% of my time was spent practicing on my own.

Great teachers may not use the preceding language of deliberate practice to describe their approach, but if they’re a truly great teacher I’d wager they’re already teaching deliberately. It’s then up to you to capture as much as you can from what they have to offer.

Deliberate Lessons

Some teachers you study with for years, others maybe just a week at a festival. Often, the critical insights happen in the practice room, but sometimes an exchange over a cup of coffee will have the biggest impact. Some tell you things that resonate immediately; with others, you might not truly appreciate the insight until years later. As mentioned above, my encounter with Cloyd Duff was very brief but ultra-high-impact. In retrospect, I wish I had a transcript of that entire session, because I’m certain a lot of what he said flew right over my 19-year-old head.

Luckily, that is now a very solvable problem! Flash memory digital recorders with excellent microphones have not only revolutionized practicing via self-recording, they’ve also revolutionized lesson-taking.

Before I elaborate, though, consider this: has anyone ever given you a “lesson on taking a lesson?” Has anyone ever sat you down and said, “You’re gonna spend a lot of time and money in your life taking lessons. Here’s how to have a really good one.”

Yeah, I didn’t think so. And that’s really weird, right?!

Well, I’d like to change that. Because if a founding assumption of deliberate practice is that “not all practice time is created equal” (i.e., sticking to the attributes blueprint will result in higher quality practice), it naturally follows that “not all lesson time is created equal.” We know this intuitively. We’ve all experienced unproductive lessons, and we’ve all experienced lessons supercharged with inspiration, revelation, and rapid growth. What distinguishes the two? I would argue the following: deliberate intention, preparation, and documentation. So here’s what I arrived at on my own, organically, as “Jason’s rules of thumb for how to have a really effective lesson”:

- CAPTURE: Record audio of your entire lesson. (Note: you must always ask your teacher’s permission ahead of time, not only as a professional courtesy, but also because in many states unconsented recording is illegal.) For what it’s worth, I never experienced a teacher saying “no.” They always happily agreed, and the best ones said, “I’m glad you’re recording this.” During the lesson, they would often comment, “You’ll want to check your playback to make sure you agree, but I think you’re gonna hear X, Y, and Z.” That is essential. Being able to hear those insights for yourself after the fact is one of the keys to rapid improvement.

.

My sense is that, as of 2018, there are a vanishingly small number of teachers who won’t let their students record. For my own students, I actually insist that they record our lessons. (And if I’m giving someone a sample lesson and they don’t record, I’ll admit to feeling slightly insulted. “What…you traveled all this way, but you don’t think this time will be valuable enough to record it?”) Nevertheless, if your teacher is in the minority who don’t let their students record, try putting it to them like this: “The reason I want to record this lesson is that you deliver an incredibly dense amount of excellent wisdom very quickly. I’m not going to get it all right away, and I want to mine it in the coming weeks, months, and years to get as much as I can out of it, because your time is that valuable to me.”

.

That naturally leads to…

.

- TRANSCRIBE: Recording is only the first step. You need to listen back to your lesson. But that’s not all — the best thing I started doing with my lesson recordings was to generate a written transcript. I would listen back from the beginning and generate a literal moment-by-moment transcript like a court reporter. This created a searchable record which proved invaluable for the future. (Pro tip: I found it was most efficient to use software like Audacity for the playback and transcription process, since you can rapidly jump between spots and add time-indexed bookmarks for later reference.)

.

- FOCUS: Re-listen to critical parts of the lesson, like major breakthrough moments, or something that you didn’t understand the first time. Review these spots multiple times, and add any extra notes or relevant commentary. Don’t be afraid to re-listen weeks or even months later. Especially profound “aha!” moments can take a long time to marinate!

.

- ORGANIZE: In my quest to master timpani audition repertoire, I had a massive amount of music to refine. In subsequent posts, I’ll elaborate on my organizational archival tracking system, but for now the gist is that most of the rep you’re dealing with will be a part of your life for a long time. Certain pieces, etudes, and excerpts will occupy extreme importance in the terrain of your musical growth, and you’ll be hiking back to those same mountains over and over again. Each of them will thus have a “living story” that summarizes the totality of your work on that specific piece.

.

Your lesson transcripts become a source of those mini-stories. After generating my lesson transcript, I would identify sections pertaining to certain rep, and then copy/paste those notes into the archive of my “living story” for that specific rep.

.

- DIAGNOSE: Proceeding through steps 2-4 honestly will likely help you assess some larger scale issues. On top of what your teacher has told you specifically in that lesson, you’ll likely starting connecting that feedback back to a previous lesson, or two, or four…and possibly even to lessons with other teachers. To the extent possible, proceed through your practice time with this feedback in mind, and evaluate self-recording from your subsequent practice sessions commensurately. That way, at your next lesson you can bring your teacher “problems to be solved” rather than simple “phenomena to diagnose.”

.

- SYNTHESIZE: In my own process of lesson-taking, I began including short postscripts at the end of my lesson transcripts — personal meditations on where that work fit into the broader scope. These ended up being extremely useful, and they were a perfect embodiment of Mr. Shermock’s “TRANSFER” philosophy. (i.e., Improving the rhythmic timpani figure in the opening of Beethoven 7 mvt. 1 helps address similar figures in Beethoven 9 mvt. 2 and Tchaikovsky 4 mvt. 1.) In Peak, Ericsson writes that the “best teachers didn't focus on particular problems but rather encouraged their students to think about general patterns and processes — the why more than the how.” So as you reflect beyond your most recent lesson transcript, try to group your problems thematically, eventually forming patterns and frameworks. And then leverage your teacher’s expertise to understand why things fit together that way.

.

The steps above require copious time and thoughtful planning. But I promise you: it will pay off. The ease and ubiquity of digital recording can revolutionize your practice room process via real-time feedback, and it can revolutionize your lessons by letting you squeeze every last drop of value out of the precious time with your teacher. (I'm convinced that previous generations would have killed for the kind of practice-enhancing tech we now get to take for granted.) When you show up to a lesson thoroughly prepared, it will be much higher impact. As a teacher, I can tell you I always have the most fun when students are highly prepared and highly engaged. The time spent is fruitful and productive. That’s high-level work. Those are deliberate lessons.

We Are What They Grow Beyond

Transitioning from “student” to “teacher” can be a strange feeling. Especially in the orchestra world, it’s a very binary process: literally in one day, you can go from being someone almost no one has heard of to someone almost everyone has heard of. And all because of one audition result.

Part of the reason it’s strange is that, to you, the process is not binary: it’s completely continuous, an incremental and grueling step by step process of improvement. And yet, all of a sudden, people now care what you think! Not only that, they want to study with you for years! (Personally, I also love stealing tricks from my students! Because the teacher-student relationship is a two-way street, and I learn things from my students all the time.)

For me, teaching is a joy, and a privilege, and an unending challenge. At the root of it, I feel that I’m lucky enough to now participate in this vast project — an epic collective undertaking of improvement and evolution. In a way, this is captured best by the line Master Yoda utters immediately after his reprimand above:

Heeded my words, not, did you. ‘Pass on what you have learned.’

Strength…mastery…umm-hmm.

But weakness, folly…failure also. Yes, FAILURE most of all.

The greatest teacher, failure is.

Luke, we are what they grow beyond. That is the TRUE burden of all masters.

It’s mind-blowingly simple and fundamental. It’s profound in that Yoda-esque way. “We are what they grow beyond.” I mean, of course! Look at any field to which deliberate practice applies: the current level of expert-level performance surpasses that of previous generations. As it should, by design. When this vast project works correctly, a teacher will have many students, and at least some of those students will end up surpassing that teacher. Not only is that how advancements can be made, that’s the only way advancements are made! Whether physics, chess, tennis, or instrumental music, evolution happens via students surpassing their teachers. One of the ways this is accomplished over time is that teachers get better at teaching, and students get better at learning. Training methods are improved, and learning tools proliferate.

In my role as a teacher, I get to participate in that collective “growth beyond,” helping successive generations reach higher and push the envelope further. No one gets there on their own…but “there” is always moving further into unexplored territory. That’s exciting. I hope my luck continues, and that someday I’ll get to fulfillingly reflect on a generation of students that have grown beyond me — a true burden, and an even greater reward. I think Mr. Shermock would agree.

![]()