(The Attributes of Deliberate Practice: Physical Limits and Sleep-Replenishing)

I have. I was a freshman at Gustavus Adolphus College. My course load was too heavy, my time-management skills not yet adequate to the task, and I compensated by burning the candle at both ends…and in the middle. I was basically the college-freshman version of Prince Valium from SPACEBALLS.

One particularly rough morning, I trudged down to my dorm’s communal bathroom facilities. The shower stalls were narrow brick-encased enclaves, like upright sarcophagi. I blasted the hot water, stepped inside, and found myself stand-slumping against the right-side wall, feet braced against the left-side wall. “This is nice,” I thought. Then I dozed off.

I don’t know how long I was actually asleep. Maybe four or five minutes. But when I woke up with the hot water still pelting my face, it occurred to me, “you know — this might not be normal…or healthy.”

It wasn’t.

And it wasn’t just limited to dozing off while standing up in the shower….

I Could Have Learned so Much More in College…and Beyond

I was a regular nocturnal presence in the music building at Gustavus. Unwisely, I only fit in my practicing late at night, once I’d already spent my day’s mental energy. I was consistently yawning before I even started my warm-ups. I was on a first-name basis with the building’s security guard, who kindly looked the other way as I habitually stayed far past the 12:00 am closing time.

It was so stupid. On the one hand, yes: I pushed myself to extraordinary lengths to get in my practice time, learn rep, and perform it in recitals. I demonstrated drive and commitment. But in retrospect, those late-night hours were heinously ineffective. They contributed to chronic sleep deprivation, and everything suffered: I was falling asleep in virtually all of my classes, I had difficulty staying focused during ensemble rehearsals, and I struggled to summon the mental acuity necessary to plow through tricky physics homework assignments. Stupid-drive and dumb-commitment doesn’t get you very far.

What this revealed was a glaring lack of self-awareness: I could have accomplished so much more if I’d prioritized better, treated mental focus like the valuable and depletable resource that it is, and simply gotten more sleep. In that case, my conscious hours could have been vastly more effective.

Instead, I doubled-down: this sleep-deprived and late-night-working trend continued through graduate school, and through the first three years of my Civic Orchestra tenure. I justified the late nights to myself with “I’m happier as a night owl,” and the lack of sleep with “I’ll sleep when I’m dead.” That bravado was fine…but not when I had things I wanted to accomplish which required intense focus.

Then, in 2008, I read Colvin’s Talent is Overrated.

I’ve previously chronicled what a game-changer that was for me. But specifically with respect to “Practicing on Empty,” I realized I’d been doing at least four things very wrong:

- I wasn’t aligning my practice times with my periods of peak mental focus.

- I was practicing past my physical concentration limit, and reaping diminishing returns.

- I remained chronically-sleep deprived…

- …and all three of those factors pointed to fundamentally deficient time management skills.

Beyond Phone-Dependency: Focus as a Casualty of Exhaustion

I previously wrote that:

“Focus and concentration are indispensable attributes of deliberate practice, and they are also in short supply. Our phones are killing our practice. We are becoming slaves to our devices.”

Slaves like Tolkien’s Nazgûl, who arguably could not focus on anything other than Sauron’s will, and thus were not very effective in the practice room. (The Witch King of Angmar had good deliberate practice intentions, but he kept getting sidetracked by constant status updates from his Minas Morgul Palantír.)

But your smartphone is far from the only thing that can diminish your deliberate practice efficiency: anything that saps, compromises, or undermines your mental focus will consequently degrade your practicing. So it should be fairly obvious that you cannot practice effectively if you’re utterly sleep-deprived and exhausted. Note that I say “should be”…with full admission that it took me over 10 years to figure out this simple truth: align your practice times with your periods of peak mental focus.

This was one of the immediate and concrete conclusions I drew from reading Talent is Overrated: I had to modify my practicing schedule. Specifically, Anders Ericsson’s study of violinists at the Music Academy of West Berlin revealed that the “best” group of violinists “did most of their practicing in the late morning or early afternoon, when they were still fairly fresh.” By contrast, the less accomplished “good” group of violinists practiced mostly in the late afternoon or evening, when they were more likely to be tired. And the “best” group “differed from the [less accomplished group] in another way: They slept more. They not only slept more at night, they also took far more afternoon naps.”

Armed with this knowledge, I committed to “being a morning person.” My goal was to log at least two good hours of deliberate practice before I left for work (my nanotech job), supplementing that with another 2-3 hours after I got home from work, depending on how much “focus gas I had left in the tank.” I also developed a skill I called “micro-napping,” wherein I would nap for as little as 10-20 minutes, but then awake feeling surprisingly refreshed for my next practice session.

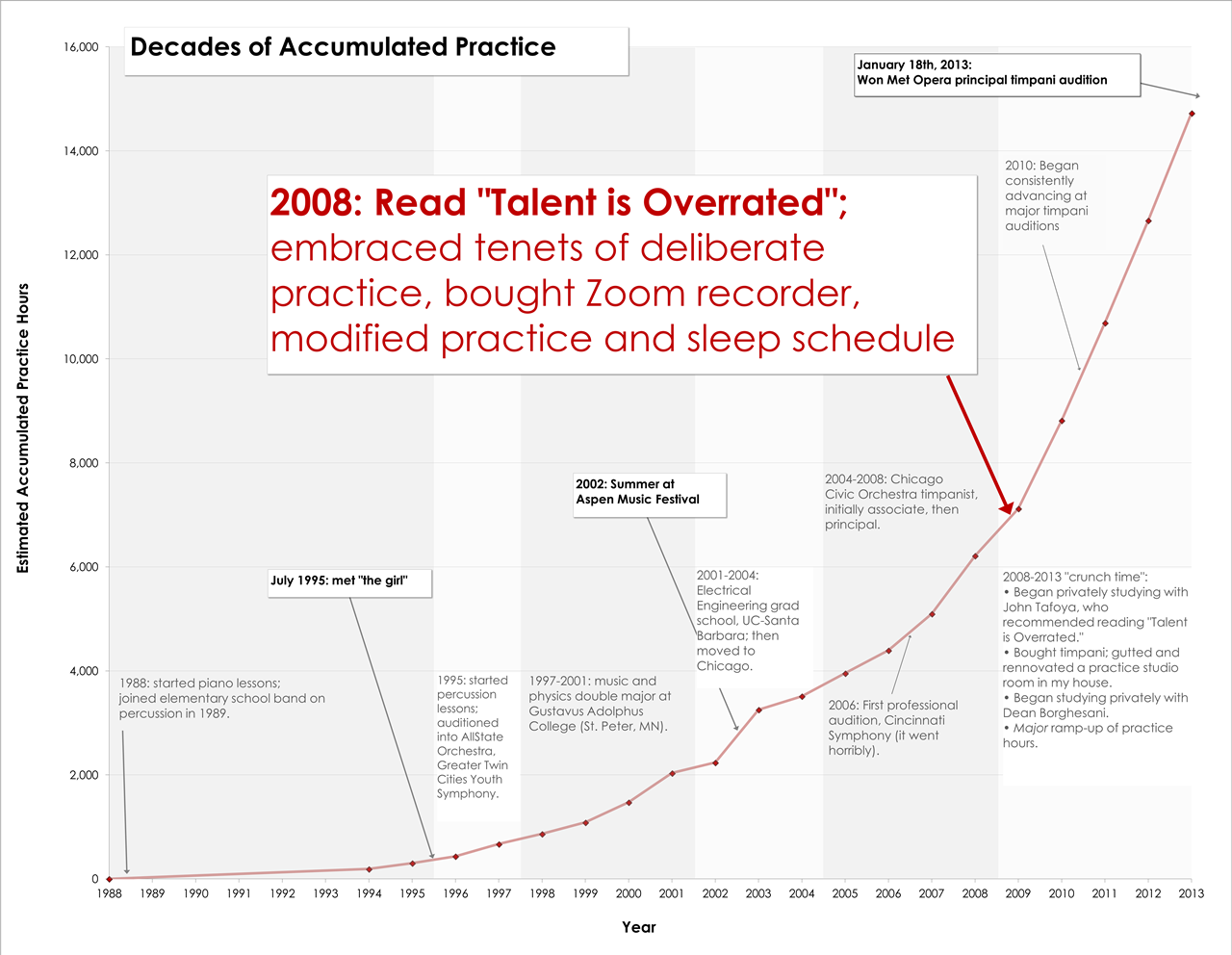

The results were dramatic, and a key factor propelling my radically increased trajectory in the chart above. I began getting much more done, much more effectively. As previously advocated, I made sure my phone was in airplane mode when I was practicing. And I began tailoring my activities to be mindful of what I call “THE WALL.”

We all know “THE WALL”: once you’ve hit it, you’re done. No amount of will, brute force, or stubbornness will get you through it. Your brain is saying “I’ve had enough! I’m outta here.” And you feel like non-thinking Play-Doh that’s been squeezed through the gasket one too many times. You’re basically worthless.

One way to view all of these focus-related deliberate practice strategies is “WALL-engineering” — accepting the inevitability of the WALL, but architecting its placement to be as far away as possible, yielding the maximum amount of productive time per day. Empirically, Ericsson discovered that morning practice sessions and robust sleep were essential to WALL-engineering. Another crucial element? Breaks. Expert-level musicians take 10-15 minute breaks, usually every 45-70 minutes. In these breaks, it’s important to disengage your brain from what you’ve been doing and turn your attention to something entirely different. Critically, however, this break activity cannot be focus-draining, and it should not be too engrossing on its own merit, lest you get distracted from your practice session entirely. (My preferred break activity was watching Ken Burns documentaries in 10 minute intervals.)

Now, there was a subtle point lurking in Ericsson’s study that turns out to have huge ramifications: the “better” and “best” groups of violinists logged the same average number of practice hours per week (24), versus the “good” group which only logged 9 average hours. (Critical point of clarification: we are strictly counting “deliberate practice hours,” where you’re in the practice room with your instrument, recording yourself and gathering feedback, and adhering to all of the other attributes of deliberate practice. But this is by no means the only time you will dedicate to refining your craft; subsequent posts will elaborate on the supporting “homework time” you can and should be investing.) Since one of the defining features of deliberate practice is its cumulative nature, it should be no surprise that the 9-hours-per-week “good” group was the least accomplished. But when comparing the “better” and “best” groups, both were practicing the same amount. So what distinguished them? Ericsson discovered that the “best” had been logging those hours for longer — they’d accumulated more deliberate practice over a longer period of time.

This makes sense in the larger framework of deliberate practice. Still, it’s surprising that “best” and “good” groups logged the same average hours: why wouldn’t the “best” practice more? Or rather, what prevented the “best” from practicing more than 24 average hours per week?

Now, to be absolutely clear, 24 hours per week is an average. It means that some practiced less, and some practiced more. In my own experience, however, under absolutely optimal conditions I was never able to exceed 35 hours per week (5 hours per day for 7 days). My average was probably closer to 24 (4 hours per day for 6 days). Like a marathon runner, I built up endurance over time, so that 2008-Jason was in the 18 hrs/wk range whereas 2013-Jason was in the 35 hrs/wk range. But that was my consistent limit. For me, that 35 hour-mark was THE WALL.

Why?

This is actually a simple yet excellent question. The research I’ve read so far isn’t entirely conclusive, but there are some fascinating suggestions: they relate to our neurobiology, and to the circuit-like wiring in our brains, and also to the mysterious empty channels in our brain tissue. But here’s what we know for sure: owing to the intensity of focus required, deliberate practice physically drains you, and there is an upper-limit to how much you can effectively practice in one day before you hit THE WALL. It varies from person to person depending on training circumstances, but in general it’s about 3-5 hours maximum. (Best advice: listen to yourself, and don’t force it when you are mentally exhausted, because practicing 2 hours at 100% focus is far preferable to 4 hours at 50%.)

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that the MET Orchestra routinely performs operas with run-times exceeding 5 hours. This past season was an excellent example: I had the privilege of performing Wagner’s Parsifal under our new music director, Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Parsifal’s run-time? 5 hours 49 minutes. The astute reader will have noticed that exceeds the upper WALL limit stated above. Indeed it does! Even though that total run-time includes intermissions — which we must carefully harness to recharge for the next act — we’re all still collectively flirting with WALL-collision. It requires serious life-engineering to ensure that the preceding hours (and days) enable maximum focus reserves by the first downbeat.

Clearly, ineffective practicing is more than simply “I’m tired, can’t focus.” But if Ericsson’s model of good deliberate practicers leaves you unconvinced, perhaps a quick tour through the underlying neurology can persuade you to avoid the mistakes of a bad practicer like me. Because I had no idea the kind of damage I was doing to myself pre-2008, but recent research begins to clarify my unfocused and sleep-deprived lunacy.

Myelin: the Essential Substance of Deliberate Practice

To begin, let’s examine the biology and chemistry of what’s actually happening when we’re deliberate practicing. Simply put, deliberate practice alters the physical nature of your brain, and in musicians the brain regions associated with aspects like tonal recognition and finger control actually grow larger. More generally, Ericsson writes “long term training results in changes in those parts of the brain that are relevant to the particular skill being developed.” And of our essential substance, Colvin writes:

“Particularly important in such changes seems to be the buildup of a substance called myelin around nerve fibers and neurons, which work better with more myelin around them. The brains of professional pianists, for example, show increased myelination in relevant areas.

“It’s significant that myelination is a slow process. Building up myelin over a nerve fiber that controls, say, hitting a particular piano key in a particular way involves sending the appropriate signal through that fiber over and over. This process of building up myelin by sending signals through nerve fibers…needs to happen millions of times in the development of a great performer. In other words, the process of myelin development seems an exact parallel to how deliberate practice works, and illustrates in a new way why it takes many years of intensive work to become a top performer…. At the most fundamental, molecular level, myelin may be the connection between intense practice and great performance.”

Here’s a simple model: your nervous system is circuitry, with nerve fibers being the wires, and myelin being the insulation on those wires. Like any electrical signaling, the signal will be faster and more accurate if the wire is well-insulated. From a neurological perspective, deliberate practice is the physical process of forming the correct pathways – new connections between existing neurons — and then insulating them over and over again until your brain/body only knows how how to do the right thing.

Myelin is critical to deliberate practice. Might it also have something to do with THE WALL?

Daniel Coyle, author of The Talent Code, explored the role of myelin in greater depth in the New York Times Magazine. Neurologist George Bartzokis offered, “What do good athletes do when they train? They send precise impulses along wires that give the signal to myelinate that wire. They end up, after all the training, with a super-duper wire — lots of bandwidth, high-speed T-1 line. That’s what makes them different from the rest of us.” Another neurologist, Douglas Fields, expanded upon this: “Every skill exists as a circuit, and that circuit has to be formed and optimized. [But myelination] is one of the most intricate and exquisite cell-cell interactions there is. And it’s slow. Each one of these wraps can go around a nerve fiber 40 or 50 times, and that can take days or weeks. Imagine doing that to an entire neuron, then an entire circuit with thousands of nerves.”

We’ve already discussed how expert-level performance requires many thousands of hours of deliberate practice. As Coyle says, “this has more universal implications. Namely, it implies that all skills are built using the same fundamental mechanism, and that the mechanism makes physiological demands from which no one is exempt.” Myelin is one of those in-demand substances, and our bodies have finite reserves. But we also now know how myelin regenerates: sleep.

Chronic Sleep-Deprivation Approximates Alzheimer’s Symptoms

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, found that “genes promoting myelin formation were turned on during sleep. In contrast, the genes implicated in cell death and the cellular stress response were turned on when the animals stayed awake.” So sleep is an essential component of sustainable deliberate practice due to myelin replenishment. If you don’t sleep, you can’t insulate those brain wires!

But that’s only part of sleep’s necessary function. Another part involves literally preventing us from losing our minds. Biologists at the University of Rochester have demonstrated that sleep plays “a crucial role in our brain’s physiological maintenance. As your body sleeps, your brain is quite actively playing the part of mental janitor: It’s clearing out all of the junk that has accumulated as a result of your daily thinking.”

For the rest of our bodies, “the lymphatic system serves as the body’s custodian: Whenever waste is formed, it sweeps it clean. The brain, however, is outside its reach…. How, then, does its waste — like beta-amyloid, a protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease — get cleared?”

This was a genuine mystery in neurology until very recently. Then, the Rochester team proposed a brain-equivalent of the lymphatic system: the “glymphatic system.” They “discovered that the brain’s interstitial space — the fluid-filled area between tissue cells that takes up about 20 percent of the brain’s total volume — was mainly dedicated to physically removing the cells’ daily waste” via “a network of channels that cleared out toxins with watery cerebrospinal fluid.” In a series of studies on mice, the team discovered that “When the mouse brain is sleeping or under anesthesia, it’s busy cleaning out the waste that accumulated while it was awake.”

Basically, sleep activates your brain’s glymphatic janitorial services, without which chronic sleep-deprivation manifests symptoms of Alzheimer’s. So, for effective deliberate practice, sleep is obviously critical: it replenishes your myelin, and it keeps you from walking around like a forgetful zombie full of brain-garbage.

Good Time Management Is More Important Than a Good Pedigree

“But sleeping takes too much time! I’m already too busy! I don’t have enough time as it is to get all my work done and prepare for these auditions!!”

I hear you. I’ve definitely been there. And I’ve fallen victim to that “fallacy of sleep sacrifice” too many times myself.

That’s why, in my experience, there is one simple factor of musical accomplishment that is so much more important than where you went to school, or who you studied with, or how early you began on your instrument: excellent time management skills.

Because with exceptional time management, you essentially create more time for yourself. You gain a major advantage, sort of like Hermione Granger using the Time-Turner to stop time for the rest of the world so she could get more work done.

You’ll have an advantage, because while it’s true that everyone has the same amount of time to prepare for an audition once the list is posted, not everyone manages their time equally well. By being a time-management ninja — by being twice as productive and efficient as the average auditioner — you’re effectively taking that 6-week audition preparation window and turning it into 12 weeks. And you don’t even need a Hogwarts artifact; google calendar will do just fine.

Once you begin applying this advantage, you can learn from all of my other mistakes: you can align your practice times with your periods of peak mental focus and knock out a couple of hours first thing in the morning; you can acknowledge your neurological limits, take sensible breaks, and maximize your hours without pushing into diminishing returns; and you can be well-rested. Go the hell to bed!

Because really – no one should fall asleep standing up. That’s just crazy.

![]()