Like every other human being with a conscience, I’ve been watching in horror as virtually the entire United States falls back into the coronavirus hellscape that ravaged New York City so ferociously in April. I’m not sure an English word exists for the particular blend of disbelief, exasperation, enmity, anguish, despondency, inevitability, and rageful numbness that accompanies watching most of the rest of the country fail to learn the lessons for which we New Yorkers paid so dearly.

It’s hard to know what to do with these feelings. One of my previous posts wrestled with our role as artists in this era of righteous protests following George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer. I contended that even though our arts institutions are riddled with pervasive racism, the works themselves reveal a totally different message: opera can and should be a powerful force for social justice, but we have an enormous amount of work to do to overcome our human failings and fulfill that aspirational potential.

In a similar way, I’ve been desperate throughout the past four months to draw any kind of meaning from the unmitigated catastrophe of Covid-19 in America. Then, several days ago, after a bout of eyeball-scorching news consumption that left me depleted and morose, an analogy popped into my mind….

The foundation for this analogy is two-fold. On the one hand, we have endless paranoid cries of “don’t trust the experts!” On the other hand, we have standard protocols for orchestra auditions. (Please bear with me.)

Any musician who’s won an audition for a major orchestra has, by definition, developed at least some degree of expertise. This expertise includes persuasively performing excerpts from core repertoire under intense pressure, supported by a foundation of musicianship cultivated through years of deliberate practice. (Musicians like these and so many others are struggling right now, justifiably concerned about a radically uncertain future, and wondering how they’ll make it through the coming months. This post is partially for them, partially for everyone, and partially a reflection on what I’ve learned from my own uncertainty-laden career transitions.)

Now, imagine it’s still the Before Times: you’re a musician with such expertise who intends to take another audition…but the orchestra announces a brand new list of totally unfamiliar music. Yikes. Then your internet goes out, your laptop starts smoldering, and a part of your precious instrument is damaged by a leaking roof. As you’re scrambling to deal with these simultaneous problems, a friend shows up knocking on your door. “Hey!” says your friend, “did you hear? They just announced the first round of prelims: you’re playing tomorrow morning. And not only that: it’s compulsory. Apparently if you don’t show up, they’re gonna blacklist you, confiscate your instrument, and sue the everloving shit out of you.”

I’m gonna go out on a limb and say that, under those circumstances, your prelim round is probably not going to sound very good.

Which is completely unsurprising. And is it really your fault? Obviously not. You, the musician-expert, were faced with an utterly unwinnable scenario akin to Star Trek’s famous Kobayashi Maru. The circumstances were a perfect storm of bad calls mixed with completely preventable outcomes based on decisions made by those in power. The context and infrastructure for your musical expertise was decimated before you ever had a chance.

Concerning your subsequent performance, we would never say “that’s a bad musician.” We would never assume “practicing is worthless.” And we would never conclude “accumulated expertise is meaningless.” To the contrary, it’s obvious that the entire scenario was structurally unprepared by design and by choice.

This is more or less the exact situation Americans have been living through for over four months. Since 2016, the Trump administration systematically dismantled U.S. public health infrastructure which had been built up over decades. Trump and his appointees gutted essential agencies, fired experts, installed non-experts in positions requiring expertise, dismantled the “pandemic team,” never bothered to read the “pandemic playbook” left by the Obama administration, and broadly disinvested in public health infrastructure…all by design, all by choice.

The conditions under which our hypothetical musician got screwed are effectively the same as those in which U.S. scientists and public health experts have been forced to confront the deadliest pandemic in a century. It’s been the worst possible “perfect storm” at the worst possible time. And, adding insult to injury (and death), it was predictable, and predicted.

Experts tried to prevent this debacle, but it was politicians that let us down. Full stop. With 142,000 (and counting) Americans killed by this virus, we should now be able to categorically state that expertise has never been more essential.

Perhaps it’s fitting that my previous post paid tribute to the memory of Anders Ericsson, the legend who spent the last 30 years of his life studying deliberate practice. It was his life’s work to better understand the specific process of cultivating expertise and expert performance. And for the last four months, we’ve collectively participated in the largest case study ever on the criticality of cultivating, maintaining, and protecting the infrastructure enabling experts to do their damn jobs.

I believe we’re living through the most teachable era in human history for the necessity of expertise itself. And if that’s true, it means that deliberate practice must play a starring role in reinvigorating expertise across all disciplines, while also safeguarding the infrastructure necessary to support the experts who will do their best to keep us safe in the future.

But until then, we’ve gotta survive.

Even Vader Wore A Mask

Say what you will about the tenets of Sith ideology — at least they were competent.

Back in 2017, Benjamin Wittes coined one of the most memorable phrases to describe the then-new Trump administration: “Malevolence Tempered by Incompetence.” Wittes’ idea was that their inherent malevolence would actually be far more destructive (Death Star anyone?) if not for the buffering effects of their total incompetence…so at least we could be slightly thankful for that.

But from the vantage point of July 2020, it’s little comfort to the families of the 3.77 million Americans who’ve tested positive for Covid-19. (And that’s only those that we know of.) The truth is that the modern world has simply never experimented with such reckless incompetence at this scale.

Now, full disclosure: I finished my initial draft of this post on April 21st. It’s been eye-opening to go through the necessary revisions this past week, because it’s helped me contextualize everything that’s elapsed in the subsequent 89 days. And I’ve got to be honest: even for as cynical and dark as I felt back in early April, I didn’t imagine we’d get to a place where our poisoned national discourse could vilify the simple compassionate act of wearing a mask. I mean, for god’s sake — as my friend Mike said the other night during our Zoom hang, “even Darth Vader wore a mask!”

Indeed. Even the Dark Lord of the Sith, the chosen one, fallen Jedi Knight, apprentice to Darth Sidious, slaughterer of hundreds of Padawan children, architect of genocide and grand inquisitor of the Jedi purge — even he wore a mask.

Masks are a tool, not a symbol. Refusing to wear a mask is like driving drunk. If 80% of Americans wore masks, Covid-19 infections would plummet. Sigh….

Nevertheless, one of the core themes of the entire Skywalker saga — and, dare I say, its related sagas The Lord of the Rings, The Ring Cycle, and countless others — is redemption. It’s never too late to do the right thing. Even after decades of unfathomably evil acts, Anakin Skywalker reemerges in the end, turns away from the dark side, destroys the Emperor, and saves the life of his son Luke. His grandson, Kylo Ren / Ben Solo, follows a similar redemption arc. As can many misguided and selfish and ignorant Americans. I hope.

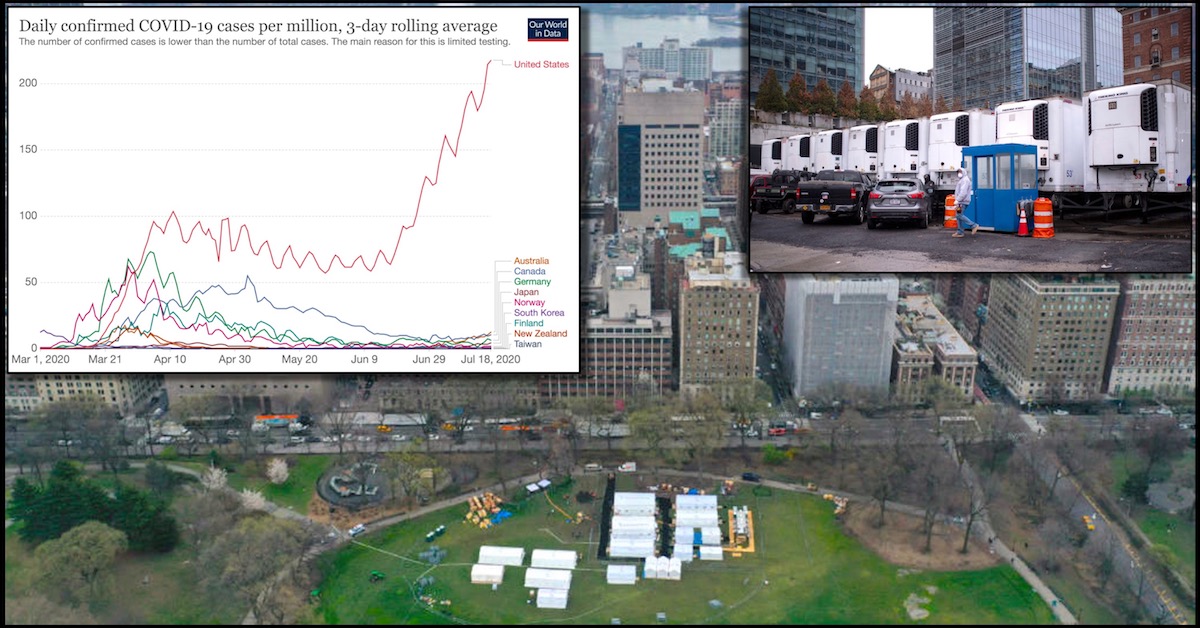

Nearly four months ago, I wrote in my journal “maybe don’t publish any blog posts until you’re less angry.” Probably good advice, but also unrealistic…because I don’t see that changing anytime soon. My goal with this post remains exploring the theme of “Expertise in the Covid-Era” (and what you can do about it). But every American should be outraged by what we’ve been witnessing. (Cacophony is great in Stockhausen, but deadly from a government failing to fight a pandemic.) I was quarantined in my upper-west-side NYC apartment for 71 days straight with good reason, as the drone of sirens constantly ricocheted between Central Park’s tent hospitals and the refrigeration trucks hosting bodies overflowing from the morgues. I’m angry that 142,000+ Americans have died from Covid-19. I’m angry about appalling racial injustice. And I’m angry that these both stem from a U.S. president who holds in utter contempt the entire notion of expertise. This is the new normal.

But you really don’t need to hear any more of these judgments from me; History Will Judge the Complicit. Moreover, Sith Lords focus on anger; instead, I am trying — really trying — to channel this anger through a recommitment to principles. In tandem with the urgent and long-overdue need for social justice, I believe this era compels us to reinvest in experts and expertise. It’s the only way out of this damn mess.

Grieving What We’re Losing, and Preparing Clear-Eyed for What Comes Next

One of my proudest moments in the MET Orchestra was organizing outreach concerts for the Manhattan and Brooklyn Veterans Hospitals with my violist colleague Vinnie Lionti. Vinnie was a pivotal member of our team: he determined viable repertoire, sourced and organized all of the music, and even guest-conducted. On April 4th, we learned that Vinnie had died from Covid-19. Then, on May 26th, we learned that Met staff conductor Joel Revzen had also died from Covid-19.

These are but two nodes of grief in a nearly infinite web of tragedy. We are all grieving, in our own ways, and with different catalysts…but this is a universal human experience right now. This will take time. And I want to honor that. I’m exhausted from being on the edge of tears for over eighteen weeks. (And that’s nothing compared to the ICU doctors, support staff, and public health officials who are orders of magnitude more exhausted, all while being harassed and receiving death threats.) I miss Vinnie and Joel. I miss Anders. And I’ll be missing who knows how many others yet to come.

Against this backdrop of grieving, I read this excellent passage from the Atlantic’s Ed Yong:

“During the Vietnam War, Vice Admiral James Stockdale spent seven years being tortured in a Hanoi prison. When asked about his experience, he noted that optimistic prison-mates eventually broke, as they passed one imagined deadline for release after another. Stockdale’s strategy, instead, was to meld hope with realism — ‘the need for absolute, unwavering faith that you can prevail,’ as he put it, with ‘the discipline to begin by confronting the brutal facts, whatever they are.’”

That has been my first major mantra since Lincoln Center shut down on March 12th: “Confront the brutal facts, whatever they are.”

Dubbed the “Stockdale Paradox” by author Jim Collins, I believe that mantra can harmonize well with other timeless life advice — “hope for the best, plan for the worst” — but only as long as those brutal facts are confronted. Hope is nice, but insufficient on its own. As Charles King put it, “the antidote to hopelessness isn’t hope. It’s planning.” So, I’m planning to “meld hope with realism.” I believe that’s the only truly viable and sustainable mindset in the Covid era. And I believe that can help us prepare clear-eyed for what comes next.

Confronting the Brutal Facts

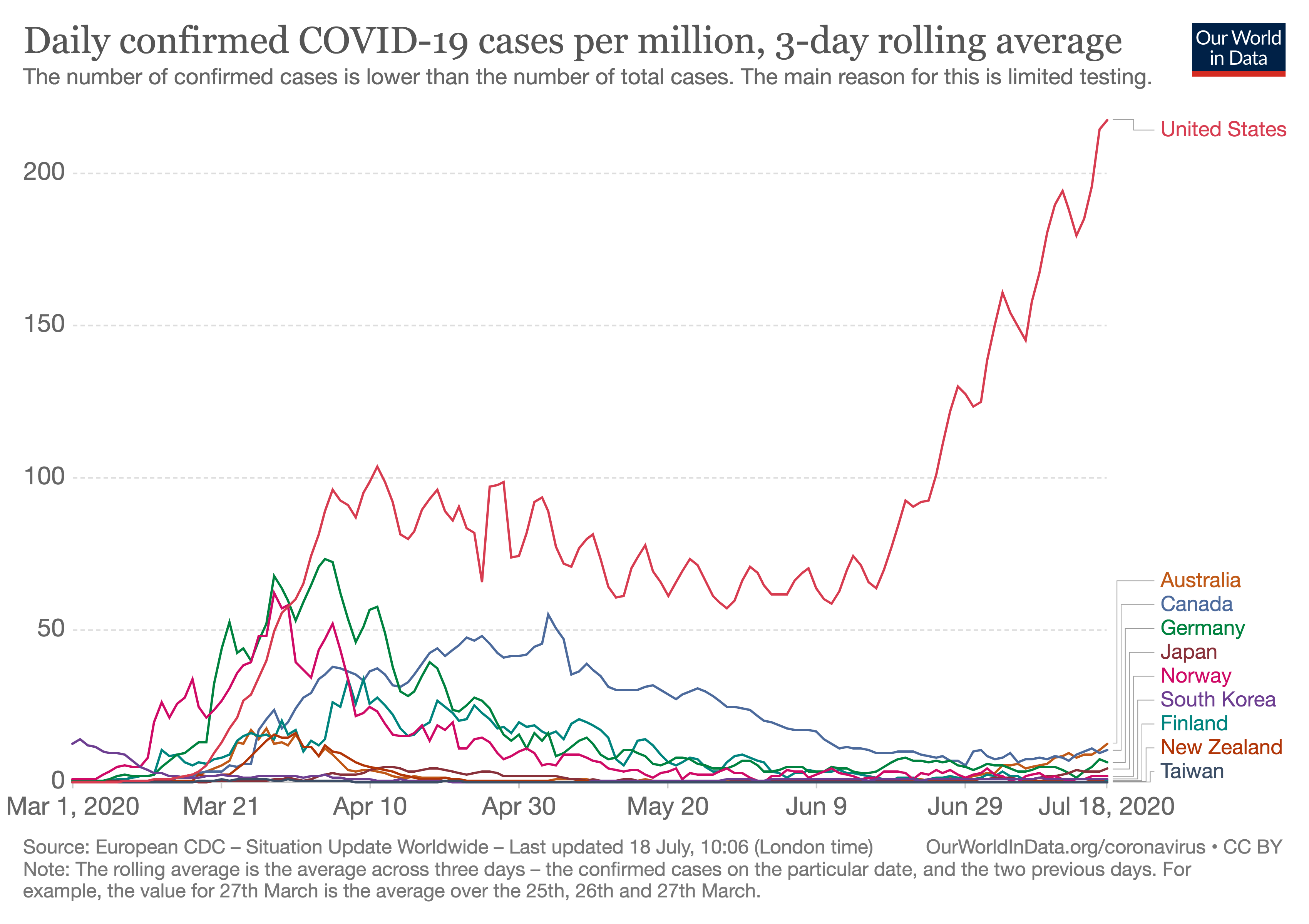

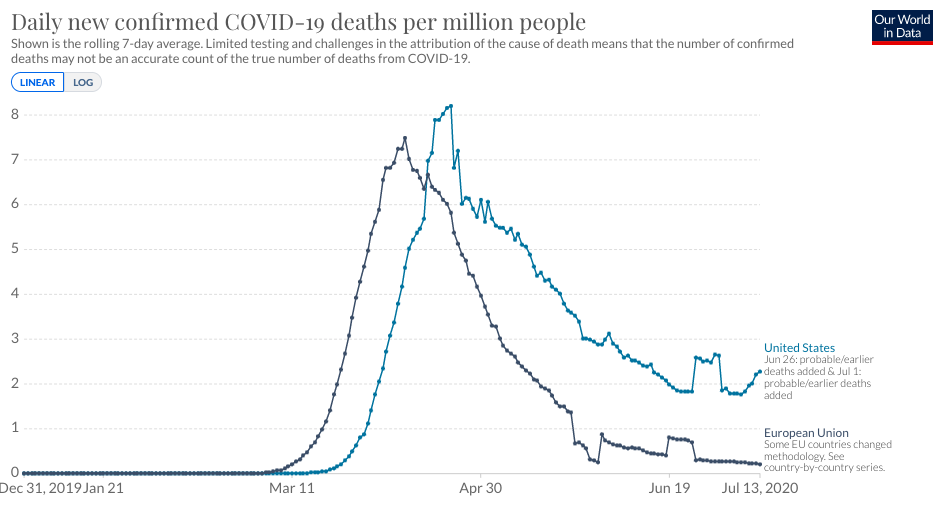

Fact: compared to virtually every other advanced country in the world, the United States is a pitiable outlier of self-inflicted mass death.

Chris Hayes: “The crisis we now find ourselves in is a human tragedy and an economic calamity. But it is also a singular national humiliation. We’re living through a moment where the U.S. is a laughing stock and a subject of pity around the world.”

Andy Slavitt: “All around the world (Singapore, Vietnam, New Zealand, Australia, Hong Kong, China, Germany, Italy, Czech Republic, Greece) [countries] have shown a simple thing— manage the pandemic and you can get back to near normal. The difference between the US and the rest of the world [is that]…while no one has responded perfectly, ours is the only government that has discounted human lives.”

Via Rick Noack: “A large portion of [Germany’s] measures that proved effective were based on studies by leading U.S. research institutes…. Health experts in countries with falling case numbers are watching with a growing sense of alarm and disbelief, with many wondering why virus-stricken U.S. states continue to reopen and why the advice of scientists is often ignored.”

Via Paul Krugman: “Per capita death rates in the US are 10x those in Europe — and ours are rising, while theirs are falling.”

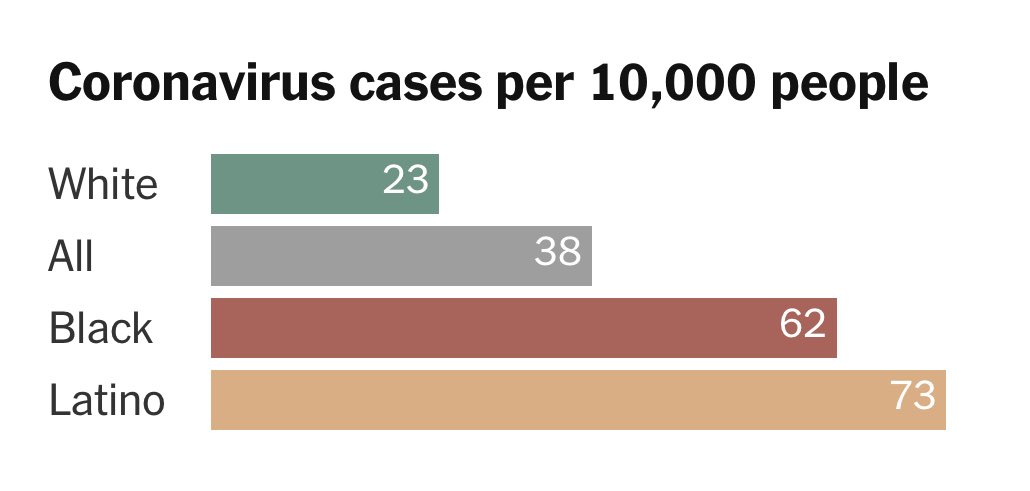

Confronting the brutal facts also reveals that Black Lives Matter — the largest protest movement in U.S. history — and Covid-19 are not really two distinct issues, but rather manifestations of the same structural rot. Of this “unifying failure,” Alex Tabarrok notes “government agencies we thought were keeping us safe and secure — the CDC, the FDA, the Police — have either failed or, worse, have been revealed to be active creators of danger and insecurity.” The Trump administration’s non-management of the pandemic has been unequivocally racist and hateful, horrifically summarized in this simple chart showing that black and brown Americans are three to four times more likely to contract Covid:

Finally, from Ed Yong: “A country that, 7 months into a pandemic, still cannot ensure that its healthcare workers have enough gowns and gloves and protective equipment is not going to be able to distribute a vaccine in an efficient way. It simply isn’t…. This is not a scientific failure…it is a political one.”

This is all incredibly depressing, but just like sitting with your instrument under your teacher’s watchful eye, we need this “real talk” assessment of where we are, how we got here, and how we move forward. As James Baldwin wrote in The Creative Process, “we have an opportunity that no other nation has…but the price of this is a long look backward…and an unflinching assessment of the record.” And just like my own late-start-trajectory in music, our broader societal starting point is not great: we exist at a moment where we lack a shared version of objective reality, tens of millions of people actively distrust experts, institutions are breaking down, our interconnected global systems are extremely fragile, and we are massively polarized.

Where do we go from here? Well, to begin with, Americans have a big decision to make in November….

As Winston Churchill Famously Said, “Definitely Give Up.”

There’s no polite way to say this: Donald Trump is a quitter, and so are his enablers.

They’re essentially anti-Churchills. Faced with a once-in-a-century crisis, they decided to quit before they ever even started. Again, even for as cynical and dark as I felt finishing draft 1 in April, I was reading takes like The Plan Is to Have No Plan and The Plan Is to “Take the Punch” with skepticism: “The administration just cannot possibly be that genocidal and self-immolating….”

And yet, here we are. “It really does feel like the U.S. has given up” is a refrain now heard from appalled public health officials worldwide. Alexis Madrigal and Robinson Meyer write “the facts suggest that the U.S. is not going to beat the coronavirus. Collectively, we slowly seem to be giving up.”

Other headlines simply speak for themselves: “How the Virus Won.” “Outcry after Trump suggests injecting disinfectant as treatment.” “Trump now says he wasn’t kidding when he told officials to slow down coronavirus testing.”

I mean, even for an opera villain, this is all really over the top….

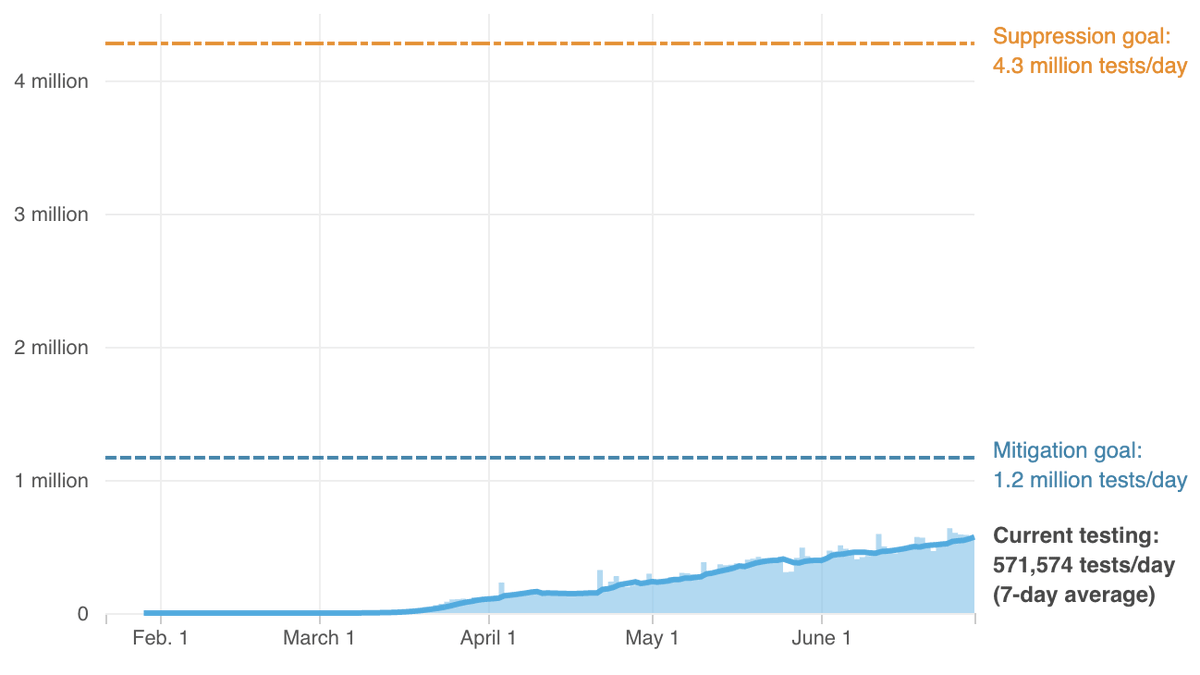

The tragedy is that testing is simultaneously the first necessary step out of this debacle, and one of the single most damning markers of Trump’s abdication of leadership. Madrigal/Meyer weigh in again: “The [Harvard Global Health Institute] said today that the U.S. must test at least 1.2 million people a day to control the outbreak and at least 4.3 million people a day to eliminate it. ‘We basically need a Manhattan Project for testing…. A nationwide, systematic strategy with a clear agency lead is desperately needed. But it’s not happening.’” This chart via NPR clarifies the scale of our urgent unmet need:

And yet….

There are many MANY Americans of conscience waiting in the wings to actually fight this virus on a coordinated national scale — experts who are desperate to right this ship. Before we get there, though, it’s worth exploring any lingering doubts from any readers who are thinking “but the CDC said no masks, and now they say masks, and they said kids were basically fine, and now kids are dying…so what the hell?”

Fair question, which I will answer with another question:

What’s the Alternative to Science?

In exploring why expertise is so essential in the 21st century, we must be honest: experts necessarily make mistakes. I would even argue that experts must make mistakes. Mistakes and failure are hard-wired into the process of learning, codified in the very essence of the scientific method.

At the level of public health policy, the hope is that “mistakes” have been worked out by that point. Thousands of hours of vetting, debate, and peer-review ideally lead to safe and accurate public health guidelines. But this system is not perfect. It can’t be. It never will be.

However, there are two factors which have severely complicated this fundamental reality in 2020:

- Non-experts occupying positions requiring expertise inside diminished institutions,

- Twitter, and the premature release of “pre-prints” (i.e., NON-peer-reviewed research).

I’ll deal with both of these in turn, but just to restate the rhetorical question: have “the experts” always gotten it 100% right? Of course not. And we shouldn’t expect them to. But even ignoring all of that, I have to ask: what’s the alternative? What’s the alternative to science??

Put another way, one of the essential things about the scientific method is that when scientists inevitably get something wrong, they do more science. The scientific method is the best self-correcting process humanity has ever developed. And since one of my previous posts argued that deliberate practice is just the scientific method applied to music, we can easily generalize this to say deliberate practice [of anything] is just the scientific method applied [to anything].

Since March 12th, I’ve been trying to partially console myself by revisiting the following logical progression:

- Sustainable life in the post-Covid After Times will depend upon learning from this decades-in-the-making debacle.

- Learning will require honestly assessing how things got this way…

- …thereby enabling the post-Covid versions of ourselves to rebuild smartly and better prepare for future crises (because they’re inevitable).

It’s basically a meta-version of the deliberate practice recipe applied to human civilization: deliberate practice requires us to learn from our individual mistakes, but this moment calls upon us to apply this framework far beyond music. If we want to get better, we must fully examine our deficiencies via focused feedback…and then make those improvements. Most broadly, the Enlightenment was about recognizing that science and rationality were applicable beyond Galileo’s proofs of heliocentrism or Descartes’s “I think, therefore I am”; science and rationality were applicable to the way we organized civilization. Instead of angels and demons and praying for a cure to an infected wound, we could have germ theory and sterilizing medical instruments. Instead of monarchies by divine right, we could have governments of the people, by the people, and for the people. This collective change in attitude — the conjoined Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment — was arguably the most impactful revolution in human history.

Diminished Infrastructure and Institutions

It was a revolution that ultimately created the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), “long considered the world’s premier health agency.” But we’ve now witnessed how incredibly fragile these institutions actually are. A devastating investigation by the New York Times reveals the consequences of stripping funding, firing highly qualified civil servants, and putting hacks in charge.

Comparing Trump’s appointee to run the CDC, Dr. Robert R. Redfield, with the Obama-era director, Dr. Tom Frieden, is a jaw-dropping case study in the importance of leadership, principle, and honest communication with the public. Prior to his appointment, Redfield had no experience running a government agency, and colleagues noted he “can’t do anything communication-wise.” Redfield’s performance throughout the coronavirus crisis has been disgraceful: after Redfield told the Washington Post that “a second wave of the virus could be ‘even more difficult’ than the first, Mr. Trump insisted that he publicly claim to have been misquoted.” In an act of stunning cowardice, Redfield backed down. I don’t envy any of these folks’ jobs right now, but I would argue that if the President doesn’t let you do your job to keep Americans safe, then you need to publicly resign. It’s pretty simple.

When it comes to the broader infrastructure of the CDC, and the thousands of dedicated experts working within the agency, those well-intentioned civil servants now range from apoplectic to just plain burnt out. Referencing one of the earliest warning signs on February 25th, Yale epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves notes that Dr. Nancy Messonnier, a director-level physician at the CDC, “told the truth…and was never heard from again.” Regarding the CDC’s elite “Epidemic Intelligence Service,” Charles Duhigg writes that “alumni of the E.I.S. are considered America’s shock troops in combatting disease outbreaks,” but E.I.S. agents have been stunned as they realized Trump was simply giving up. They spend their careers running pandemic simulations, but no one ever thought to simulate the scenario where the federal government simply does nothing — it was too unfathomably crazy. Unsurprisingly, “morale at the C.D.C. has plummeted…. Everyone I talk to is so dispirited. They’re working sixteen-hour days, but they feel ignored. I’ve never seen so many people so frustrated and upset and sad. We could have saved so many more lives. We have the best public-health agency in the world, and we know how to persuade people to do what they need to do. Instead, we’re ignoring everything we’ve learned over the last century.”

This didn’t passively happen to the CDC. It was done to the CDC, by design and by choice.

James Fallows has written more broadly about the parallels between the debacle of the 2003 Iraq invasion and the Covid crisis, particularly how both the Bush and Trump administrations were unwilling to heed experts’ warnings in advance. Fallows notes that we had previously been “very well prepared for the [Covid] crisis we’re now dealing with…but the whole system had a ‘single point of failure’: it relied on a national government that cared about the public health risk, and was willing to learn and act.” In a final resonant echo, and separated by only 15 years, the parallels between the CDC’s Redfield and Hurricane Katrina’s “Heckuva job Brownie” are painful, and not coincidental. Yet we Americans keep not learning these lessons, continuing to empower the people and the party that bring disaster upon us over and over again.

So, we must be extremely clear: there are legitimate experts, and then there are people installed in positions requiring expertise, and these are not the same thing. Politically appointed hacks and apparatchiks don’t count, and they’ve already done tremendous damage wielding power in positions requiring expertise they don’t possess. Experts are getting fired, loyalist hacks are being installed, and this is systemically horrifying.

Legitimate vs. Bullshit Expertise

What happens, though, when a non-expert claims “I have expertise” when they obviously don’t? Who makes that call?

As it turns out, researchers have studied taxonomies of expertise. Expertise cultivated through deliberate practice is what we would call “legitimate.” This contrasts with “bullshit expertise,” my nickname for the paradigm articulated by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahnehman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. In discussing the world of finance and the research that led to the dictums of passive index investing, Kahneman brutally dissects how “nobody beats the market” over a long enough time frame, especially highly-paid money managers. He notes that “a major industry appears to be built largely on an illusion of skill,” and the illusion of validity — two cognitive fallacies with special places in his comprehensive book because they invite such enormous risk. (Michael Lewis’s book The Big Short exhumes those specific financial risks in gory detail.) Contrasting with all of this, Kahneman notably highlights doctors, scientists, and musicians as professions that require and build “legitimate expertise.”

Since the onset of this pandemic, frontline medical professionals, epidemiologists, and virologists have emerged as obvious heroes. (To this I would absolutely add social justice activists and leaders, since their legitimate expertise is essential to navigating these interspliced crises.) They are all the real life versions of The Avengers I’ve often referenced in previous posts…except in reality these heroes acquired their superpowers not by divine gift or spider bite, but rather by cultivating their expertise deliberately.

Every evening at 7p, New Yorkers hollered out their windows to cheer our city’s medical workers.

Again, the heroes rescuing us from global pandemic are experts via deliberate practice.

It’s impossible to overstate how important this is. An ICU doctor has engaged in many thousands of hours of deliberate practice, as have nurses, lab techs, virologists, epidemiologists, and professors of public health. They possess legitimate expertise built through deliberate training — training which necessarily incorporates corrective feedback loops, thereby enabling them to learn from mistakes. That’s how you know it’s not bullshit.

The reason deliberate practice is the unique avenue to legitimate expertise is because expertise is more than just knowledge. I previously wrote about how frameworks of domain-specific knowledge are necessary, but insufficient on their own — you actually have to do something with that knowledge. You put it into action via mental representations. That is the essence of expertise. That is what we so desperately need right now. And these Avengers’ professional lives channel this expertise not just to “make more money,” “get more clicks,” or “score higher ratings” — their expertise saves lives.

But what of the conflicting information from well-intentioned experts? What of “face masks are not that effective” followed by “the coronavirus could be ‘under control’ in weeks if everyone wore masks”?

Science and Twitter Go Together Like Toothpaste and Orange Juice

At a basic level, I never, ever want to penalize anyone for learning from their mistakes. Lord knows I’ve made many of my own, and it’s not necessarily a pretty process. So I would vastly prefer public health officials learn-as-they-go than never learn at all.

But beyond that truism, our 21st century technology has uncomfortably collided with the mechanisms of science. Remember my auditioning analogy from the top? Let’s revise this thought experiment: as before, the orchestra announces a brand new list of totally unfamiliar music. With more normalcy, though, you’re now given 6 whole weeks to prepare the list. “Great!” you think to yourself. “This is something I can manage.” But then your friend shows up again: “Hey! Did you hear the orchestra is dispatching a media team to broadcast every single minute of your practicing to the world via YouTube live? Wild, huh??”

We musicians have honest-to-god nightmares about scenarios like these. Deliberate practice is an inherently solitary — even intimate — activity. Making real progress requires you to bare your soul, lower your shields, and appear “sonically naked” to yourself. In the Before Times, we would practice thousands of hours in private, rehearse hundreds of hours in semi-private, whereafter the audience would (ideally) get to witness a polished final product. So, the idea of the world watching me hack my way through a brand new excerpt on day 1 is frankly mortifying.

But right now, scientists are in the real-life grip of this nightmarish scenario. Via social media and early-release research papers, the world is watching their day-1 practice play out in real-time. And it’s messy.

That’s because real-life science actually works much the same way music does: behind the scenes, in labs, at conferences, and through the peer review process…science is messy. There’s squabbling, head-butting, egos, mistakes, flawed analyses, and plenty of hand-wringing. Speaking about his excellent piece Why the Coronavirus Is So Confusing, author Ed Yong notes that “science is ‘less the parade of decisive blockbuster discoveries that the press often portrays, and more a slow, erratic stumble toward ever less uncertainty.’ Scientists disagree. They have it out, and they oscillate toward a shared understanding. We in the press make those oscillations look bigger than they actually are by covering every incremental development as it happens — and I’m not sure that, during this crisis, that’s the best route toward greater public understanding.”

The whole point of the peer review process — the underpinning of all scientific work since at least the 1700s — is slow, careful deliberation, without conclusions being leaked ahead of time. Again, the beauty of the scientific method is that it’s generally self-correcting. By the time the public sees any of the “science,” it should have been argued over for years (if not decades), vetted, and peer-reviewed…finally resulting in a degree of consensus. That’s the equivalent of the “opera performance.”

So, a major cause of these spiraling eruptions of public confusion is that science was never designed to be done through social media. All hell seems to be breaking loose because virology and twitter do not mix. We’re witnessing the equivalent of an opera audience watching not our polished performances of Bohème from January, but rather me 7 years ago in the practice room hacking through it for the first time.

It was never meant to be this way.

What’s the solution? How would I have handled it myself if twitter had been prevalent during my nanotech days? I honestly have no idea. Scientists are only just beginning to grapple with the seismic shift precipitated by social media. (Climate scientists are wryly telling their public health colleagues “hey, welcome to the club!”) But if the plight of journalists is any guide, scientists may continue grappling with this for years without any clean solution. As has happened so often recently, Silicon Valley prefers to leap first, then “look,” and then offer “good luck with that!”

Nevertheless, in reaffirming the ongoing necessity of legitimate expertise in the modern world, sci-fi author Kim Stanely Robinson points out that “when disaster strikes, we grasp the complexity of our civilization stuff – we feel the reality, which is that the whole system is a technical improvisation that science keeps from crashing down.” The consequences of this are very clear-cut, and we need to be honest about the stakes: no one knows the eventual Covid death toll, but it’s already needlessly too high because non-experts have been in charge, and legitimate experts have been systematically ignored or fired. And this really isn’t debatable. This is not a matter upon which reasonable people can disagree. It’s just a simple statement of brutal facts.

Thus, our conclusions cannot and must not be “don’t trust the experts.” The only sane conclusion can be “the environment for expertise has been profoundly degraded by the equivalent of a deepwater horizon oil spill, and modernity is unsustainable without radical cleanup efforts.”

Tackling the Problems Once We Have Actual Leaders

There was a time when a benevolent superpower spread peace and prosperity throughout the lands of all the free peoples. This reign of might seemed permanent, unstoppable even. But then the Great Plague struck, precipitating a long, slow, steady decline until what remained was barely a shadow of its former glory. Desperate to save his own skin, a false-ruler colluded with a hostile foreign power, rendering himself the puppet of a foreign tyrant, and nearly brought about the total collapse of the west.

This was the condition in which Gandalf found the realm of Gondor in the year 3019 of the third age (TA), beaten down and resigned to defeat. Denethor II, Steward of Gondor, had promised to “Make Gondor Great Again,” all while secretly colluding with Sauron via palantír. But in fairness to Denethor, the decline of the Gondorian realm predated him. The gradual erosion occurred over thousands of years, from its zenith under “Ship-King” Hyarmendacil I (TA 1149), to its nadir 1870 years later under Denethor’s own suicidal hand. Middle-earth scholars will cite various reasons for Gondor’s decline, but the Great Plague was undeniably the proximate cause. In TA 1636, King Telemnar horribly mismanaged Gondor’s pandemic response, and subsequently died from it. The famous White Tree withered and died too. Facing mounting losses on all fronts, successive generations of Kings were forced to move the capital from Osgiliath to Minas Tirith. Their military was so decimated that they could no longer tend the forts and garrisons guarding Mordor, and thus began its repopulation by orcs and other foul beasts. Shortly thereafter, Mongol-like Wainriders blew in from the east like a calamitous storm. In another fateful blow, Minas Ithil was captured by the Nazgûl, thus becoming the dreaded Minas Morgul. Finally, only eight reigns after the onset of the Great Plague, the line of Kings ended when Eärnur rashly departed to face the Witch-king of Angmar in single combat, never to be seen again.

The War of the Ring nearly ended the Kingdom of Gondor permanently. Had it not been for the expertise of Aragron, Galadriel, Elrond, and Gandalf, the kingdom of men would have been overrun. Thank goodness for deliberate wizardry.

Like Tolkien’s version, Wagner’s Ring Cycle invokes a similar arc: throughout the course of four operas and many decades, Wotan steals a ring of power from his archenemy (Alberich) and then reneges on a deal with his contractor (Fafner) while continuing to indulge the toxic fantasy that he can bullshit his way out of the mess he’s created…but the reckoning is inevitable.

Back in our real world, it’s obvious that our current American woes didn’t arise overnight — our reckoning has also been decades in the making…and was equally inevitable. Unfortunately, we don’t have Hobbit allies to throw rings of power into volcanoes, nor do we possess the power of the Rhine to simply rise up and reboot and wash everything clean again. What we do possess, however, is the ability to empower experts…and we can vote to do so in November. Actual leaders are waiting in the wings, eager to start rebuilding. It is not too late. Recall the meta-version of the deliberate practice recipe applied to human civilization: we must learn from our mistakes and apply the deliberate practice framework far beyond music. Moreover, as a matter of feedback, assessment, and improvement, Americans deserve a full scale accounting after this nightmare turns the corner, with the kind of consequences and accountability we never had in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

And then? We will need to tackle these problems, and far more quickly than the festering-timespan in which they’ve grown. Time is relentless in its linear push, and it doesn’t care whether all we want to do is lie on the floor in the fetal position.

Specific to musicians’ circumstances, it is already July, and many of us have big decisions to make soon. For example, students: enroll in the fall? Delay a semester? Take a gap year? Or, orchestral musicians in NYC: stay put? Get out of the city to somewhere cheaper? Start assessing alternate careers and supplemental income streams? Real decisions must be made, even amidst ongoing shock and processing and grieving.

How do we even begin to think about this? How do we prepare clear-eyed for what comes next? Especially when that future is so radically uncertain??

Navigating Radical Uncertainty

I regret that I don’t have a solid answer for you. And even if I did, I wouldn’t presume to prescribe it because this kind of navigation is inherently individualized and tailored. But I’m happy to at least offer how I’ve been thinking about it for myself. If my first mantra has been “confront the brutal facts, whatever they are,” my second crisis-mantra has been this: “In the face of radical uncertainty, the most valuable new currencies are adaptability, flexibility, and sustainability.”

These ideas have been governing nearly all of my conscious decision-making since March 12th. They’ve helped me sort out the noisy descent from the illusion of modern stability to “failed state” reality.

How do we achieve flexibility and sustainability? For musicians specifically, I hope it can start by recognizing the true nature of our skills. I think too many musicians needlessly assume their training is narrow and their skill sets are limited; to the contrary, I firmly believe musicians possess diverse skills by definition, and I propose that the Covid era now compels us to explore the broadest possible applications of these diverse skill sets.

What terrain are we navigating? I start here: the virus suppression plans noted above now assume (1) widely available testing (at least 4 million per day), and (2) robust federally coordinated contact tracing and isolation. This has not been happening, nor should we have any reason to believe it will magically start happening. (At least until January 2021…if we’re lucky.) Lacking federal coordination, Governors are fundamentally hamstrung by lack of resources, the legal requirement to balance their budgets, and the implausibility of coordinating 50 different contact tracing databases.

What about a vaccine? Well, even in a crisis, science takes time. The most brilliant virologists in the world are throwing all of their wits and resources at this problem, but I’m nevertheless reminded of a famous anecdote (Brooks’s Law) from my scientist days: “While it takes one woman nine months to make a baby, nine women can’t make a baby in one month.” Some processes just can’t be expedited. We’re likely 16+ months away from a widely-available vaccine, and even then it may not be fully effective. And reprising Ed Yong’s insight from earlier: “A country that, 7 months into a pandemic, still cannot ensure that its healthcare workers have enough gowns and gloves and protective equipment is not going to be able to distribute a vaccine in an efficient way. It simply isn’t.”

This only reinforces what the most qualified public health experts have already been saying for months: we are not going back to “normal” anytime soon.

For me, this has prompted some truly agonizing conversations with students — aspiring musicians who want nothing more than to get back to refining their craft, at a school, playing in ensembles with other aspiring musicians. Hewing to my initial mantra of “confronting the brutal facts,” and prioritizing their own safety above all else, I’ve been passing along advice from the best-informed and most conscientious epidemiologists and professors of public health I can find: via the Washington Post, “There is no safe way to reopen colleges this fall…. Every way we approach the question of whether universities can resume on-campus classes, basic epidemiology shows there is no way to ‘safely’ reopen by the fall semester. If students are returned to campus for face-to-face instruction, the risk of significant on-campus covid-19 transmission will be unmanageably and unavoidably high.” Similarly, Daniel Drezner writes “I have yet to see a viable university plan for reopening colleges for in-person instruction this fall…. None of these plans seem to acknowledge that a) 18-year-olds will act like 18-year-olds; b) many of them are likely to be mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic spreaders of the virus; c) the question of a flare-up of cases on campus is not about ‘if’ but about ‘when’; and d) quarantine and tracing procedures break down once a significant fraction of the student body is infected.” Graeme Wood notes that the true value of a college education comes from the fact that college is a “superspreader event” by design. “Without the [in-person] mixing…a university education can be little more than a very expensive library card.” But perhaps the most damning indictment comes from Harvard. In reaction to the Trump administration’s aborted (and heinously cruel) effort to deny F-1 visas to international students unless they attend in-person classes, Matt Stieb notes that Harvard is not even trying to offer in-person instruction. And “if Harvard, with its crimson prestige and an endowment that tops $40 billion, is unable to hold courses in person, it’s quite unlikely that other schools without those assets will be able to do so.”

To be clear, if Harvard cannot safely provide in-person instruction, no one can. Be wary of anyone or any institution claiming otherwise.

A Tournament, A Tournament, A Tournament of Lies

R.E.M. has been one of my favorite bands since the early 90s. As Michael Stipe so memorably sang, “It’s The End of the World As We Know It.”

A tournament, a tournament, a tournament of lies,

Offer me solutions, offer me alternatives, and I decline,

It’s the end of the world as we know it (time I had some time alone)…and I feel fine…

I don’t think there’s any going back to exactly the way things were in the Before Times. Even the word “unprecedented” is starting to lose its gravity, because we’re running out of ways to illustrate that nothing remotely like this has ever happened at this scale. Historian Kevin Kruse has called it “Disaster Voltron.”

We’ve experienced parts of this before, just never all at once.

As others noted, it’s like the Spanish flu of 1918 and the stock market crash of 1929 at the same time, but overseen by Harding’s total incompetence plus Nixon’s pettiness and paranoia.

It’s like Disaster Voltron. https://t.co/tc6GHpF6Yk

— Kevin M. Kruse (@KevinMKruse) March 13, 2020

Thinking about the ongoing interwoven catastrophes is like pulling the strands of a thousand different sweaters. Trying to comprehend the scope of loss is like staring at the night sky and reminding yourself that the visible stars constitute only 0.0000045% of the 100 billion stars in just the Milky Way galaxy, which rounds down to 0% of the estimated 1 septillion stars in the universe. It’s the definition of incomprehensible.

Michael Stipe posted as much on March 17th:

Message from Michael… Longer version on https://t.co/UXmfpJhgaJ pic.twitter.com/0LSWqTU6Eq

— R.E.M. HQ (@remhq) March 18, 2020

I don’t feel “fine” — that’s a tall order right now — but I am trying to feel “steady.” Or clear-eyed. Or maybe stoic.

In the midst of radical uncertainty, the shape of our collective future is the murkiest it’s been in decades. But even though predictions are difficult, I firmly believe this: whatever our world looks like post-Covid, it’s going to require overwhelming legitimate expertise to get us back on a positive trajectory. Deliberate practice is the process of cultivating legitimate expertise in any discipline…and it may well be the best possible recipe for ensuring your own nimble adaptability throughout the Covid-era.

What the World Needs Now is Experts, and Deliberate Practice Cultivates Expertise

One of my previous posts noted that “history is a flat circle” — that our fights are rarely novel, and that humanity wrestles with the same basic basic problems century after century. I argued that The Arts reveal this cyclicism via timeless stories, reminding us that the struggle will inevitably find us again.

Well, now it’s our turn. Now it’s our struggle, and our burden to bear. Consoling a reluctant Frodo (who wishes “none of this had happened”), Gandalf intones “so do all who live to see such times, but that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.” We Americans have been given this moment, and it is our responsibility to reaffirm the imperative of expertise and the indispensability of legitimate experts.

As recently noted by the president of Germany’s national academy of science, “The United States [still] has some of the world’s best and brightest minds…. The difference is, they’re not being listened to. It’s a tragedy.” But that can change. It must change. This is when we can realize that what the world needs now is deliberate practice…sweet, sweet deliberate practice.

I’m really not trying to be glib here. Since my first post, I have tried to make the case that deliberate practice is not limited to music: it is a recipe for cultivating expertise in anything.

We need this now more than ever before.

Turning once more to the Atlantic’s indispensable Ed Yong, he writes “America isn’t just facing a shortfall of testing kits, masks, or health-care workers. It is also looking at a drought of expertise, as the very people whose skills are sorely needed to handle the pandemic are on the verge of burning out.” He elaborates further: “I’ve seen public-health folks caricatured as finger-wagging ivory-tower alarmists, distinct from the everyday [people] affected by their advice. False. Dichotomy. The experts I spoke to [are going through it all too], feeling trapped at home, missing their families. Public-health — and especially the folks who specialize in pandemic threats — is not a big field. There’s only so much expertise to go around, and it’s not infinite.” And then, the kicker tweet from Gregg Gonsalves: “Show some love to your epidemiologists, disease modelers, infection control experts. There’s a lot of punching down on this platform. Public health people aren’t in a lucrative profession…we just try to do our jobs with what we’ve got.”

I believe that our Covid-era is demanding compassion, flexibility, and adaptability…from everyone, in all fields, everywhere. Cultivating existing expertise and/or rapidly developing new skills is becoming a universal imperative. Getting ourselves to a sustainable post-Covid life will need to involve a healthy global dose of deliberate practice.

As a friend once said, “the problem with FDR’s ‘We have nothing to fear but fear itself’ is that fear is scary!” Indeed. One of Daniel “Legitimate-vs-Bullshit-Expertise” Kahneman’s legacies is prospect theory, notably the insight that human beings are instinctually awful at assessing asymmetric risks. (e.g., The upside might be nice, but the downside is catastrophic.) So, in these scary and chaotic times, we all must evolve to become better at assessing asymmetric risk, and contemplating courses of action in medium to bad to worst-case scenarios.

As we plod through daily news onslaughts, I’ll be doing my best to adhere to my own advice: remain calmly rational in the face of crisis, confront the brutal facts, and remember that embracing the core tenets of deliberate practice can help inoculate you against the ravages of future uncertainty.

And lest this all seem too grim, I want to clarify one final thing: while it goes without saying that musicians face a more daunting future than at any time since World War II, I do not believe The Arts are going to evaporate. The Arts are fundamental to our basic humanity. Our collective quarantine has witnessed an explosion in free online streamed performances, including the Met’s Nightly Opera Stream. The demand clearly remains, and people are hungry for those experiences. As Peter Dobrin wrote, “Wondering about why classical music was struggling for relevance, [Wolfgang Sawallisch] floated the theory that modern life was so full of easily obtained pleasures that music had become divorced from the impulses and urgent conditions that produced it. For better or worse, that may no longer be a danger. Everything we hear now…seems fraught. A dip into Strauss’ Metamorphosen today sends a chill up the spine. What seemed bleak before is full-blown postapocalyptic…. Almost everything in the orchestral literature…suddenly seems about human connection.”

It’s never been clearer that the arts “are a kind of mirror of humanity,” and the need for reflected human connection and compassion has never been more urgent. So even though the institutions are facing the greatest existential shock since their modern inception, I am confident The Arts will endure.

Until then, the world is going to need experts, of all varieties. And being truly good at practicing the violin or trombone or timpani means much more than just vibrating air from those instruments — it means that you’re good at learning. You are good at cultivating skill and expertise. Our world is going to depend upon it.

Non-experts created the context and conditions for this catastrophe. Experts will get us out of it, and hopefully shape the world that comes after.

Stay healthy, stay safe, and be well.

![]()

What Can You Do?

In a word, introspect.

.

Give yourself time and space to think. Write in your journal. Assess your feelings honestly. Summon all possible compassion for the lives afflicted by the coronavirus, and all possible solidarity with those aching for social justice.

.

At various times since the inceptions of these crises, I’ve had to remind myself to take a step back, with plenty of time to breathe, ultimately making space for my thoughts to manifest and evolve before taking any action. As part of your own process, if you do decide to take any action, I would like to offer the following opportunity. In a postscript to my previous post honoring Anders Ericsson, I included the following: “Ever since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, I’ve been struggling to determine how I might be able to help, or give back in any meaningful way…. As a way to honor Anders’ memory and his colossal contributions to our field, I’ve decided to offer a pay-what-you-can online Deliberate Practice Bootcamp. The weeklong seminar is open to all instrumentalists, August 3-7, 6:00-7:30p edt each evening, with proceeds donated to ArtistRelief.org and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund.”

.

Especially relevant to the preceding blog post on the role of expertise in the Covid-Era (and what you can do about it), I’ve been spending a lot of my time thinking about how to help my fellow musicians who are struggling. Having watched all of our work evaporate in a matter of days, we’re sitting here four months later with no sign of that work returning any time soon. The entire American performing arts sector is red ink as far as the eye can see, and government support has ranged from laughably inadequate to nonexistent. In the best of times, we artists grappled with serious questions about the future economic viability of our art forms…and these are not the best of times.

.

Specific to performing arts institutions, the consensus of virtually all public health officials is that we’ll be the last to reopen. It is difficult to imagine droves of opera fans packing densely into the Met’s 3800 seat auditorium without an effective and widely-available vaccine. Evidence indicates that “superspreaders (5-10% of infected) drive 80% of infections, superspreader events are significant drivers (large crowds & bars)…and choirs & singing, close quarters, poorly circulating air all contribute to infection.” Even the Met’s own general manager has told the New York Times “I can’t imagine any scenario in which performances can take place at the Met when social distancing is still a factor.” I do not presume to speak for my Met colleagues, but it’s safe to say that many of us are now accepting this as an involuntary 18+ month unpaid sabbatical. And none of us have any idea what the performing arts sector is going to look like in September 2021….

.

So, while I stand by what I wrote above — “I do not believe The Arts are going to evaporate” — the reality is also that “musicians face a more daunting future than at any time since World War II.” What can musicians be doing to support themselves until the After Times?

.

I’m not sure anyone can provide totally concrete answers, but I am hopeful that the Deliberate Practice Bootcamp ONLINE might offer some possibilities, or at least some ways to think about those possibilities. I intend to elaborate upon my contention that musicians’ true skills are broadly applicable, based on my 10 years of experience as a full-time scientist. I’ll be leaning into connections between adjacently applicable areas like process engineering, technical writing, public speaking and education, audio/video production, intellectual property law, digital rights management, public relations, and non-profit management. And I will go into detail about my own uncertainty-laden career transitions. Again, I firmly believe musicians possess diverse skill sets by definition, and I propose that the Covid era compels us to explore the broadest possible applications of those skills — skills we cultivate best via deliberate practice.

.

So, please consider joining me online later this summer to honor Anders Ericsson, and to explore how deliberate practice might help musicians weather the Covid storm.

Explore the Deliberate Practice Bootcamp ONLINE