But for one reason or another, the perception of a “scientist” among orchestral musicians can miss the mark, sometimes by a hilariously wide margin. I’ve met orchestral players that seemed to assume that I used to fly around the lab with a cape and safety goggles, leaping tall buildings of data in a single bound, x-ray-visioning complex problems, and then curing cancer…all before lunch. Oh man — if only.

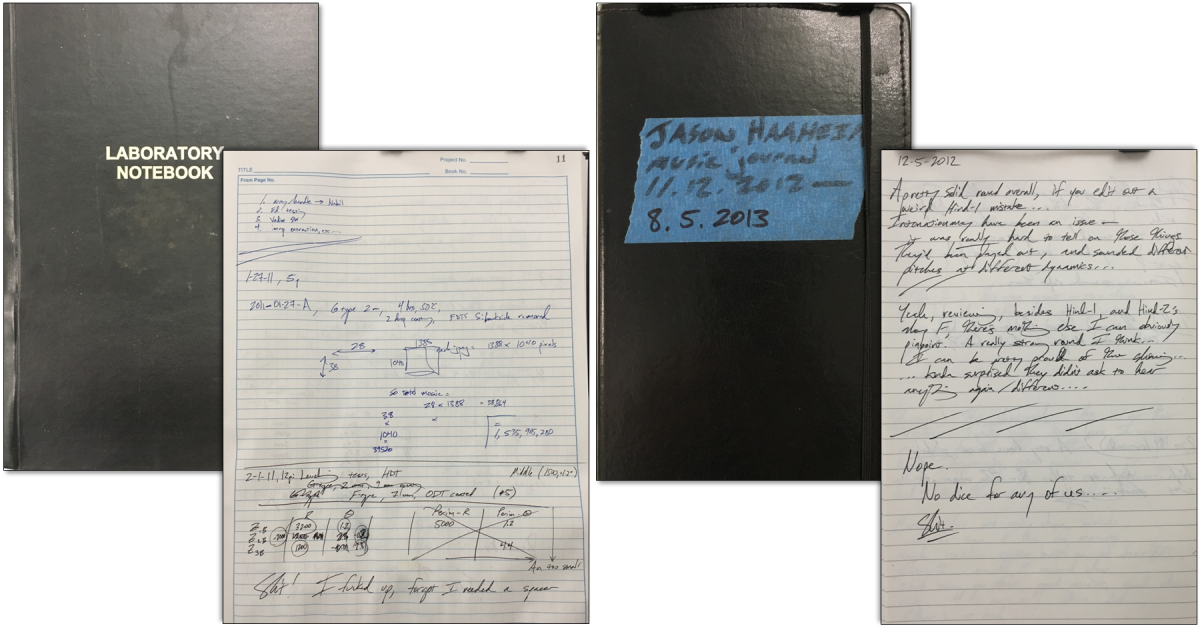

“No,” I sadly reply. “I’m afraid it’s not quite that glamorous or exciting….” There are cubicles. Lots and lots of cubicles. Inevitably harsh fluorescent lighting. Meetings. So many meetings. TPS report cover sheets. Bosses named “Bob.” And failure. Mostly failure. Day after day, week after week: failure. Most of science and engineering is things not working…and then scratching your head to try and figure out why. One of the keys to ultimately figuring it out is taking good notes. Keeping a good lab notebook. Rigorously, scrupulously documenting your failures. Organizing your records meticulously so that you can map out the terra incognita of what didn’t work, ultimately helping to navigate you toward what might work. And then once something seems to work? Be skeptical. That’s pretty much it. That’s science. That’s the scientific method: have an idea, test it out, it doesn’t work, document how and why…repeat…and maintain healthy skepticism along the way. Persistence is key.

So, most of science is well-documented failure.

And for anyone who’s taken orchestral auditions, most people will admit that they’ve lost more than they’ve won. Those are just the basic statistics of a highly competitive field. Olympic athletes are already incredibly high level performers, but most do not win the gold medal. Defined that narrowly, most Olympians fail to win gold. Orchestral auditions are no different.

So, most of auditioning is failure.

Considering my dual experience in science and music, it took me an embarrassingly long time to put this together. I’d been in my nanotech job for more than 5 years before this realization started to dawn on me. Not coincidentally, this was also the same time I read Talent is Overrated by Geoff Colvin — a book that changed my life. (I’ll detail the book and its lessons extensively in future posts.) But I eventually had this basic cognition: “Most of science is well-documented failure, and most of my auditioning has been failure. Hmmmm. Perhaps I should at least apply the ‘well-documented’ part to auditioning.”

I’ll get into that in future posts, but this basic observation radically changed the trajectory of my musical life. It was a major inflection point. And like many of these “Aha!” moments, it seems incredibly simple in retrospect. I previously wrote that science is a state of mind, a way of thinking about problem solving. Put another way, science is dedicated to improving a thing — specifically, our understanding of the natural world. But interpreted more broadly, scientific thinking is applicable to improving many kinds of things; I applied it to improving as a timpanist.

In my first post, I wrote that any perceived success is just the tip of a massive iceberg of failure. In science, major discoveries, peer-reviewed papers, and patents represent the tip of that iceberg. In music, it’s people like me with careers in the MET Orchestra. Doing what we do in music, it’s pretty much mandatory to constructively embrace failure…because you’ll likely be doing a lot of failing!

Now unsurprisingly, I’m a highly analytical person, but that should not set me apart from being an artist too. I propose that that is a woefully misguided stereotype: successful musicians don’t just sit there and “feel the music at you real hard.” Most musicians are more analytical and “scientific” than they realize. Artistry is supported by craft, and craft is supported by analysis.

I’ll detail that sort of auditioning analysis in future posts. But for now, go find a cubicle, gut a fish, and embrace that failure!

![]()

2018-04-09 update:

The concept of this post — as featured in the above-linked podcast — is featured as the Forbes “Quote of the Day”!